There are more housing units in the development pipeline in Lancaster city than at any point in recent memory, data from the city’s Department of Community Planning & Economic Development Department indicates.

The department has either approved or is in the process of reviewing projects totaling 1,282 housing units, and developers have proposed projects totaling another 1,971, for a total of 3,253, Director Chris Delfs told the audience at the Lancaster City Alliance’s Downtown Merchants meeting this week.

That contrasts with recent history: Just 167 units have been built this year, and just 314 since 2018.

To be sure, there are headwinds, Delfs said: Interest rates are rising, and the cost of labor and construction materials has spiked nationwide.

Still, “I feel really, really bullish and excited about what I have heard” in discussions with developers and business leaders, Delfs said. “… I think the sky’s the limit.”

In a follow-up interview with One United Lancaster, he said he’s encouraged that in most cases, developers are willing to fund their projects through private investment, rather than seeking tax exemptions or other city subsidies. That speaks to the improvements in the city’s economic health over the past couple of decades, he said.

Housing was a priority for local policymakers even before the pandemic. Since 2020 the urgency has grown more acute as rents tick upward and vacancy rates hit record lows.

Of particular concern are the city’s and county’s shortages of affordable housing. The U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development estimates the county would need to add more than 1,000 affordable units a year for 16 years to meet demand.

The city’s five-year interim housing plan, released last year, calls for creating 2,000 new housing units by 2026, with at least 15%, or 300, being affordable. Adding units “of all kinds and all price points” will help stabilize housing costs, Delfs said.

Delfs highlighted nine upcoming projects in his presentation. Of them, one is 100% affordable: The Apartments on College Avenue, a 64-unit complex by nonprofit developer HDC MidAtlantic, budgeted at $16.4 million.

Another, Landis Place on King is raising money to make eight of its 79 units meet affordability criteria. Landis Communities has received more than 70 applications for those eight spots, spokesman Larry Guengerich said.

HDC is planning other affordable projects in and around the former St. Joseph Hospital campus, which is being redeveloped by private firm Washington Place Equities. Ben Lesher, the developer of the Yards project at the former Lancaster Stockyards, is exploring making some of the 200-plus units there affordable.

Building affordable housing involves engaging with federal regulations and subsidies, so it’s generally more expensive and complicated for developers, Delfs noted.

Standard economic analysis suggests that lower-income households benefit indirectly from the construction of market-rate housing, because the increase in housing supply helps to moderate rent increases. Despite some affordable-housing advocates’ concerns that new high-end housing can drive rent hikes in the rest of the market, the balance of empirical evidence indicates that it doesn’t.

Much of Delfs’ presentation covered demographic and economic information that’s being compiled for the city’s comprehensive plan.

Census data indicates that Lancaster city’s population is younger and more diverse than the county’s or the state’s as a whole. It’s growing more diverse, but it’s aging, too, Delfs said.

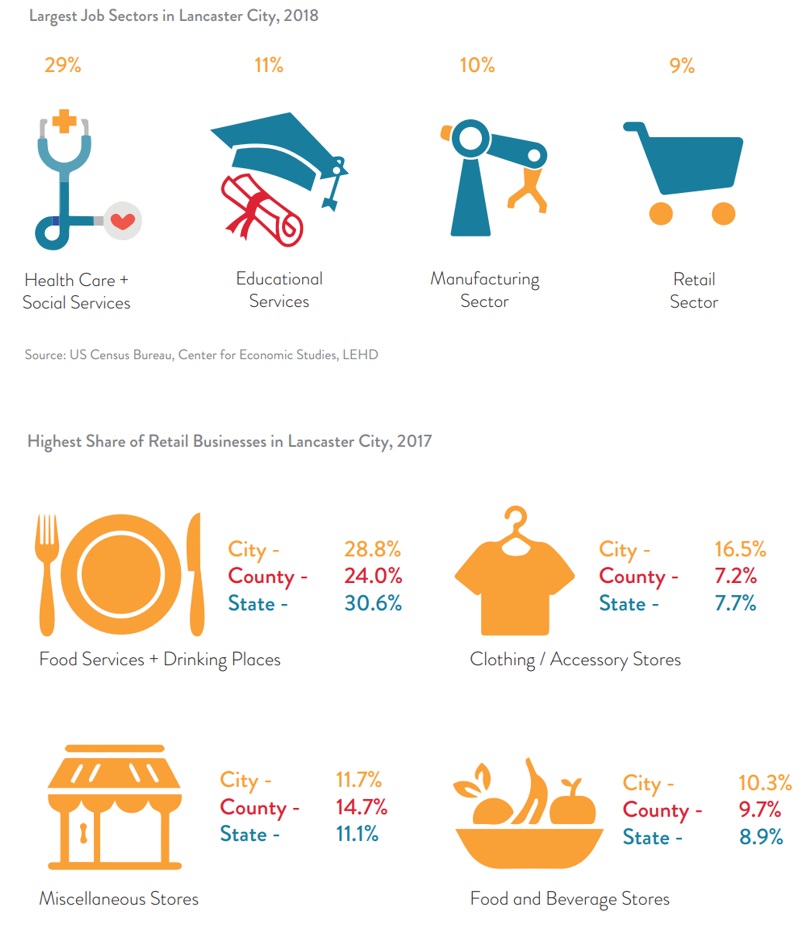

Health care, education and manufacturing account for half of city jobs. In the retail sector, bars and restaurants dominate, accounting for nearly 29% of all retail businesses as of 2017.

Surely those numbers have changed, given the retail industry’s struggles during the pandemic, several audience members suggested. The post-pandemic data, however, shows that Lancaster’s retailers, including bars and restaurants “really held up well,” Delfs said.

Lancaster City Alliance President Marshall Snively concurred. While there could still be a delayed effect from the pandemic, he said, through 2020 and 2021 the alliance’s data indicates there were more city retail openings than closures.