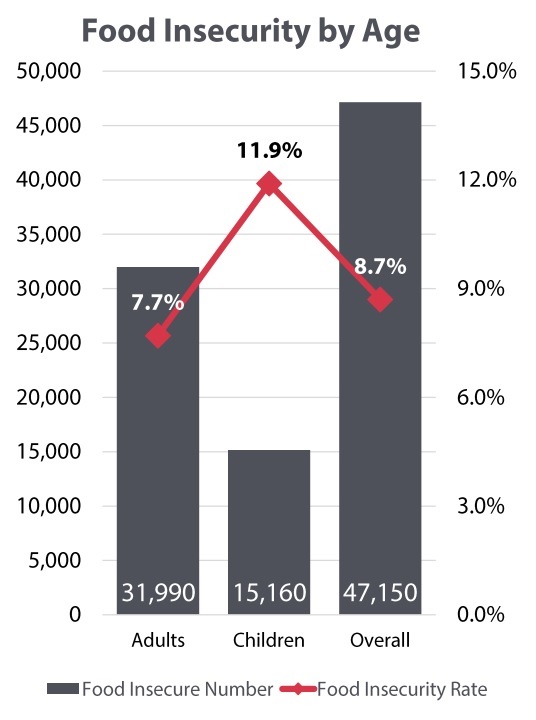

More than 15,000 children in Lancaster County — nearly one in eight — face food insecurity.

Black and Latino individuals are 3.5 times more likely than Whites to be food insecure (21% versus 6%).

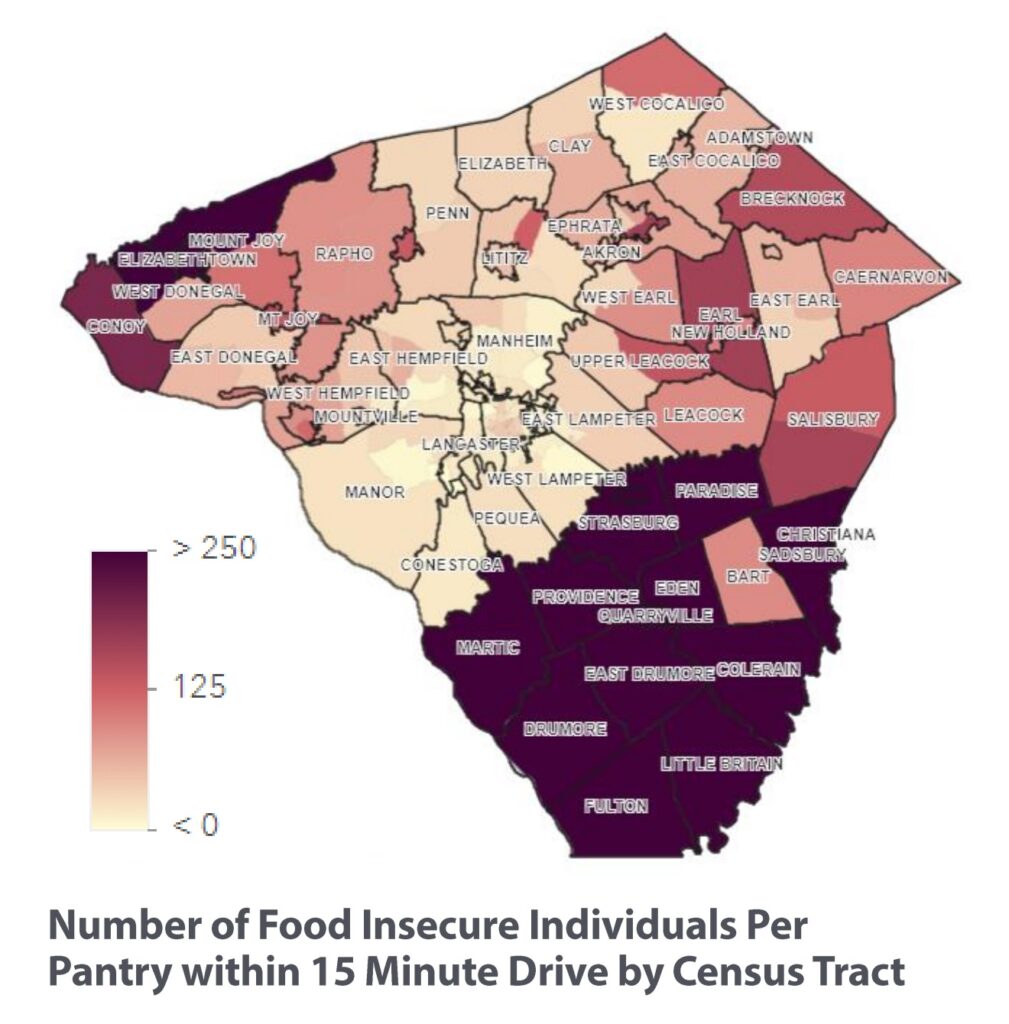

Several areas of Lancaster County have limited access to food pantries, an issue exacerbated by pantries’ limited evening and weekend hours and geographical restrictions on who can receive food.

Those are some of the principal findings of the Lancaster County Community Hunger Mapping Project. Undertaken by the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank in cooperation with Hunger-Free Lancaster County and other local nonprofits and foundations, it is the most detailed and ambitious analysis of food access in the county to date.

Among other things, it incorporates one of the first analyses in the country of utilization gaps at the census tract level, said Zach Zook, the food bank’s senior policy research manager.

Zook and Dawn Watson, the food bank’s policy research coordinator, presented an overview of the project findings at the Hourglass Foundation’s August First Friday Forum. The food bank and Hunger-Free Lancaster County are planning to unveil the full report later this month at an event Aug. 22 at Southern Market Center.

The mapping project has been a year in the making. The Food Bank analyzed reams of state and federal statistics, which it set alongside the information from its own extensive data collection. That effort stretched over four months and included household surveys, focus groups, one-on-one interviews and anonymized data from local pantries. (Some of the survey data was collected through United Way of Lancaster County’s PA 211 East hotline.)

Looking at the data

According to Zook’s and Watson’s presentation, more than 47,000 individuals in Lancaster County, or 8.7% of the population, live in food insecure households. Children are 55% more likely than adults to be food insecure.

The Food Bank defines “food insecure” households as those which either “reduced the quality, variety and desirability of their diets” (low food security) or reduced the food intake of one or more members (very low food security).

Income is the strongest determinant of food insecurity, Zook said. The vast majority of food pantry patrons either work full-time or receive Social Security or disability benefits. Among those who work full time, nearly half earn less than $24,000 a year.

Nationally, the food insecurity rate spiked during the Great Recession of 2007. It has gradually ebbed since then, but for the past two decades it has never fallen below 10%.

Demand on food banks spiked in the early days of the pandemic, but was offset by massive infusions of federal aid, including enhanced unemployment benefits and enhanced Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, or SNAP. Those enhancements have since expired, and advocates say demand is again trending upward.

Partnership potential

The report identifies a number of “significant opportunities” to promote collaboration and coordination among Lancaster County’s food banks. Among its recommendations:

• Cover access gaps: Large swaths of southern and northeastern Lancaster County have limited access to food pantries. Providers should collaborate to bolster pantries in those areas. Additionally, several pantries have geographic restrictions on whom they serve; those should be reduced or eliminated.

• Increase operating hours: Nearly 1 in 3 food-insecure individuals don’t have easy access to pantries with weekend hours, while 1 in 4 don’t have access to pantries with evening hours.

• Lower access barriers: Two-thirds of pantries require photo ID, nearly half require proof of residency, and some require classes or meetings with social workers. Many limit visits to once a month. Food pantries “should strive to be the lowest barrier social service organizations,” and should evaluate their practices accordingly, Zook and Watson said.

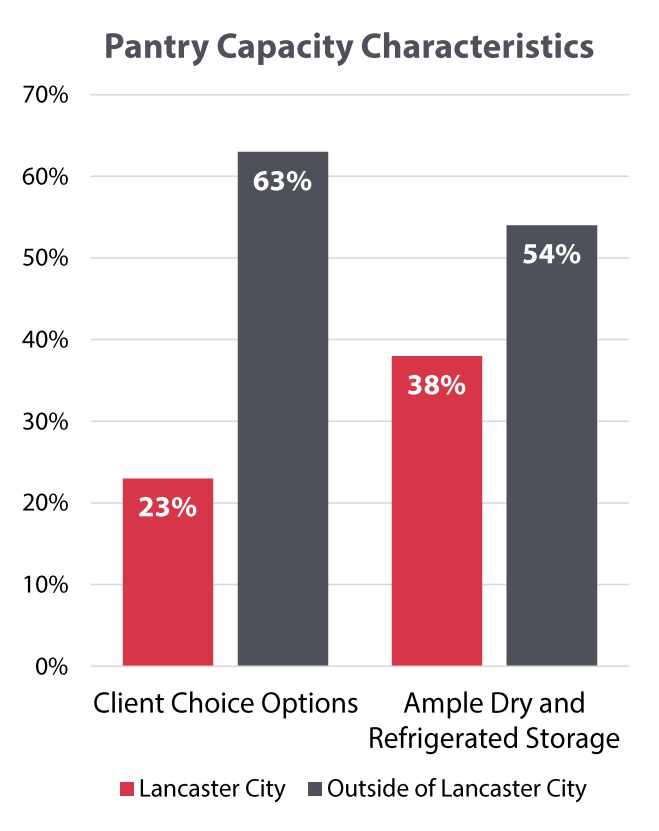

• Improve food pantry equity: Food banks in Lancaster city have less storage capacity than their county counterparts and are less likely to let clients pick out their own items. The charity food network should take steps to remedy those drawbacks.

Generally, food pantries are trusted and appreciated in the community, but some patrons report negative interactions, primarily with volunteers. Better volunteer training and assessment can help ensure that every guest is treated with courtesy and respect, Watson said.

When volunteers are rude or disapproving, “those experiences stick with people,” Watson said.

Several of the areas identified in the report as having limited access are along Lancaster County’s borders. Perhaps there are food pantries across those borders that would solve residents’ access issues? By and large, there aren’t, Zook told One United Lancaster, and visitation data indicates that cross-border pantry use is very limited.

Federal benefits

Encouraging participation in other programs has the potential to reduce reliance on food pantries, the report says. Lancaster County’s utilization of SNAP and the Women, Infants & Children Program (WIC) is among the lowest in Pennsylvania, creating an opportunity for food pantries to sign up their eligible clients.

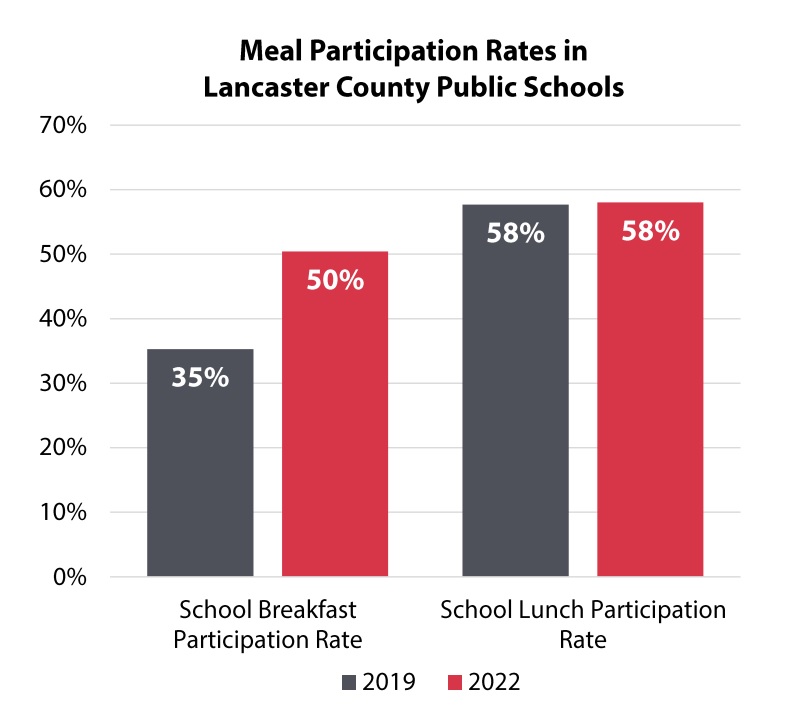

Similarly, Pennsylvania now provides universal free school breakfast to all students and is working to increase access to free school lunch for eligible students. Participation rates are trending upward, and that’s a positive sign, the report says.

Pantry visitors report having to choose between paying for food, utilities or rent, and evictions and forced relocations are common. Hunger-Free Lancaster County should consider developing eviction prevention initiatives, the report says.

The expanded federal child tax credit dramatically reduced food insecurity and child poverty, but was allowed to expire at the start of 2022. Social service agencies should campaign for its reinstatement and for similar policies “that prioritize agency and dignity,” the report says.

Asked which policy changes he thinks would help the most, Zook said nationally, it would be the reinstatement of the enhanced child tax credit; and locally, more SNAP signups and the expansion of food pantry hours.