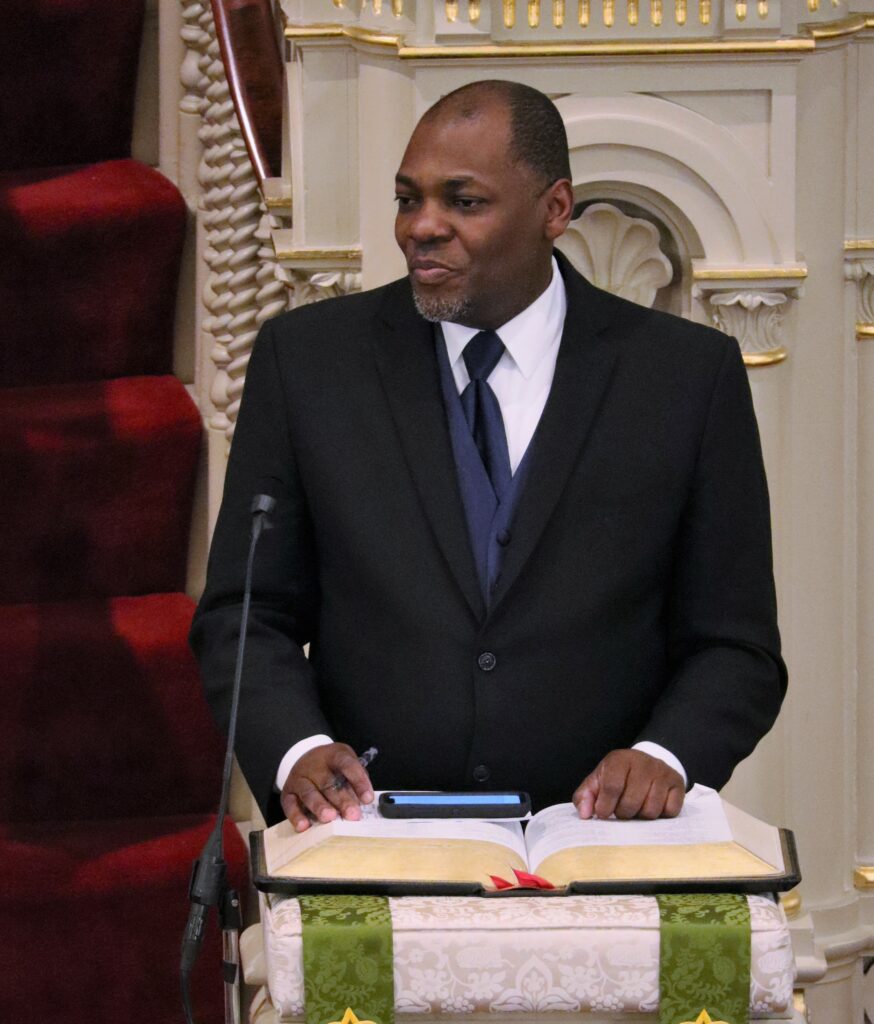

The goal of the NAACP “is the betterment of mankind,” Lancaster branch President Blanding Watson said.

The Lancaster NAACP, founded in 2023, turns 100 this year. The organization is celebrating with a gala from 6 to 9 p.m. Thursday at the Holiday Inn Lancaster. (For more information, click here.)

Part of the festivities will be a presentation summarizing the organization’s history in Lancaster. The event’s theme is “Growing Equity, Growing Stronger…The Journey Continues.”

The struggle for civil rights in Lancaster has often mirrored the struggle at the national level: the turbulence of the 1960s, a backlash in the 1980s and 1990s, and, recently, the Black Lives Matter movement.

There are iconic battles and warriors in this struggle, like Nelson Polite Sr. and the 1963 protests of segregation at the Rocky Springs pool. But just as important, Watson said, are the NAACP’s less well-known victories, like its support for local employees who alleged discrimination at R. R. Donnelley Printing.

Another example, says Watson, were lawsuits filed on behalf of local citizens in opposition to Pennsylvania’s 2012 Voter ID law.

The Lancaster Branch NAACP’s charter was granted in June of 1923, 14 years after the NAACP itself was formed in New York City.

At that time Abram Polite, father of Nelson Polite Sr., was the president of another organization, Lancaster’s Negro Civic League, which had formed in 1917 by the Rev. F.T.M. Webster.

The Negro Civic League presaged the work of the NAACP: lobbying for black police officers to join Lancaster’s force, advocating for black property ownership, and providing childcare for working black parents.

In October of 1943, Lancaster’s New Era reported that the NAACP took a survey to determine the housing situation of Black residents. Even those engaged in war work, the survey found, had trouble finding places to live, where overcrowding was the rule rather than the exception.

Throughout the 1940s, Lancaster’s NAACP advocated for Lancaster’s Black population on issues including housing, politics and civil rights. It hosted public meetings and talks featuring clergymen, labor activists, and others. Often these presentations were held at the Crispus Attucks Community Center, which opened in October 1942.

Leroy Hopkins, a retired professor of German at Millersville University, is one of the most prominent scholars of local Black History. According to Hopkins, Lancaster’s NAACP lapsed sometime in 1949. It was revived in 1960 by Ashleigh Dudley, who had helped to bring Hall of Fame baseball player Jackie Robinson, the first Black player in the Major Leagues, to Lancaster for a public address.

Hopkins, citing Dudley, suggests the lapse may have been the product of communist witch hunts.

In 1962, under chapter President Kenneth Bost, a string of protests and demonstrations began. Many people know about the marches at Rocky Springs, which took place in the summer of 1963.

That same summer, Bost organized protest marches up and down King Street, through downtown Lancaster’s commercial center. These protests targeted the Watt & Shand and Hager & Bro. department stores, which the NAACP accused of refusing to hire Black people as salespersons. They led to store officials pledging “good faith” in hiring without regard to race.

It was during this tumultuous time, Karen Dixon said, that she got involved with the NAACP. Over many years she served the organization in a variety of roles.

In the early 1960s, Dixon said, she was invited by her sister to attend meetings. She started hanging out with other young people in the movement, especially at 120 S. Queen St., where in 1967 Lancaster NAACP President the Rev. Ernest Christian had started a “Freedom House,” a youth center and coffee shop designed to serve Lancaster’s young people of color.

She recalled an incident that happened to her when she graduated from middle school. Many years later, she would retell it to school classes throughout Lancaster County as part of an NAACP program of oral history presentations about the Civil Rights Era.

“We had a field trip to celebrate, and we visited Gettysburg. After an excursion in Maryland, we stopped at a diner to eat. There was a sign on the wall that said ‘Whites Only.’ My teacher asked the owner if all the students could eat together. The owner said no, that the Black kids had to eat in the back.

“My teacher said, ‘Then we’ll all eat in the back.’ At first we were really upset … but actually that back room was the nicest room in the building! I had never experienced that kind of blatant racism. We always had racism here in Lancaster, but it was more subtle.”

Dixon became an NAACP youth member, then joined the organization formally once she turned 18. She remained interested in the organization’s work throughout the 1970s. Her involvement deepened in the 1980s, and she eventually became an officer and board member.

Dixon worked closely with Rita Smith-Wade-El, mother of state Rep. Ismail Smith-Wade-El, on educational projects. Dixon recalls Smith-Wade-El taking buses of students to historically Black colleges and universities, HBCUs, to get a firsthand look before they applied to colleges.

Lancaster’s NAACP worked throughout the 1980s to encourage adoption of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday after Gov. Milton Shapp declared it a state holiday in 1978.

President Ronald Regan signed the law marking the day as a federal holiday in 1983. It was first observed at the national level 1986.

The Rev. Ronald Taliaferro, who had become Lancaster’s NAACP president in 1984, lobbied the School District of Lancaster to observe the holiday.

As late as 1989, several school districts in Lancaster County still stayed open on MLK Day, including Penn Manor and Hempfield. Rita Smith-Wade-El pointed out their policy in a Feb. 27, 1989, article in the Lancaster Intelligencer Journal.

Smith-Wade-El, who served on the NAACP’s executive council at the time, said schools weren’t doing enough to teach children about non-Western perspectives on history. In response, she held a four-hour workshop for SDOL teachers, hoping to provide ideas for multicultural education.

When the Ku Klux Klan marched through downtown Lancaster in the summer of 1991, a Unity Day was organized in protest. The Rev. Harvey Sparkman III, elected president of Lancaster’s NAACP in 1988, was one of the speakers.

When the Klan threatened to return in 2001, the Rev. Edward Bailey of Bethel AME, helped to organize another counter-protest. Men of all races filled the steps of the Lancaster Courthouse. Dixon remembers that day’s action with a good deal of pride. The Klan was thwarted, reduced to staging a small rally in Quarryville.

White allies, like Ellen Griest (wife of W. W. after whom downtown’s Griest building is named), have been part of Lancaster’s NAACP since its inception. Betty Tompkins, a white English woman, left her church (St. James Episcopal) in order to join Bethel AME and went on to join the NAACP and work on its behalf. Dixon referred to Tompkins as her adopted mother and said she and her husband “exemplified what a Christian ought to be.”

Watson has been the chapter president since 2010. Looking toward the future, he remains focused on holding corporations to their stated Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion policies. This means bolstering mentorship programs for youth students of color, arranging for job shadowing opportunities, and encouraging participation in STEM and careers in which people of color remain underrepresented, like medicine and finance.

He’s concerned about the ongoing fight over fair public education funding in Pennsylvania as well as the national debates over “critical race theory,” social justice and civic education. For Watson, it shows the continued need to address the teaching of Black studies in schools at all levels.

“African American history is American history,” he said.