Update, March 15: On Wednesday, the Lancaster County commissioners voted unanimously to have the county participate in the new round of national opioid settlements.

Previously reported:

Lancaster County could receive up to $12.9 million over the next 10 to 15 years from the next phase of the national opioid settlement, county Solicitor Jackie Pfursich said Tuesday.

As before, the amount received will depend on how many jurisdictions participate in the settlement. And once again, time is tight, Pfursich told the county commissioners in her briefing during their morning work session.

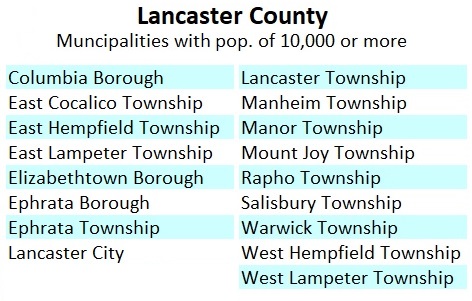

To qualify for the additional money, the county has until April 18 to sign and file the settlement documents, she said. For it to receive the maximum amount, the 17 county municipalities with populations above 10,000 must do so as well.

That was true the first time around, too, which means all the municipalities have gone through this process before and are familiar with it. They are registered on the settlement’s online portal, Pfursich said, and are receiving the necessary documents and email notifications.

Depending on their meeting schedules, some may have to call a special meeting to vote on joining the settlement by the deadline, she said.

The three commissioners agreed it makes sense for the county to join the settlement. A resolution to do so is on their agenda for Wednesday morning’s meeting.

About the settlement

The settlement’s first round is bringing Lancaster County roughly $16 million over 18 years. The new influx of money would come from five defendants: Manufacturers Teva and Allergan and distributors Walmart, Walgreens and CVS. (The first round included manufacturer Johnson & Johnson and distributors AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson.)

The new round’s terms are similar to the one before. In return for being cleared of liability for the nationwide opioid epidemic, the five corporations will make payments to states for distribution locally, with the money used to combat the epidemic’s ongoing effects.

Nationwide, CVS and Walgreens have agreed to pay more than $10 billion, and Walmart agreed to pay $3.1 billion. Allergan has agreed to $2.4 billion and Teva, $4.25 billion.

Once counties and municipalities decide whether to opt in, the states and the defendants have the opportunity to decide if participation is broad enough to move forward. If it is, the defendants will make their first payments to states this summer. Lancaster County can expect its initial share of the payments to Pennsylvania toward the end of the year, Pfursich said.

Setting priorities

To decide how to spend its settlement money, the county convened a working group last year. The effort was led by Parsons, who co-chairs Joining Forces, a coalition of local entities battling the opioid epidemic.

The other co-chair is Alice Yoder, executive director of Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health, who is seeking the Democratic nomination for county commissioner this spring.

Along with other stakeholders, they developed a framework consisting of five priority funding areas:

A) Neonatal abstinence support: Hiring a caseworker to help mothers mitigate the effects of prenatal exposure to opioids.

B) K-12 support: Hire additional assessors for the Student Assistance Program, which provides voluntary substance abuse assessments and treatment referrals.

C) Diversion support: Fund Pathways to Recovery, the county’s diversion program for low-level nonviolent drug offenders.

D) Support for the county Drug Task Force

E) Support for medication-assisted treatment at the County Prison.

To date, the county’s settlement funding has gone toward items A, C and E. At the time, the commissioners said they wanted to be conservative in their initial allocations — future settlement funding is somewhat uncertain, as a firm payment schedule hasn’t been established — and the Student Assistance Program and the Drug Task Force had other funding sources and less immediate need.

With up to $12.9 million in additional funding now expected over the next 15 years or so, should the plan be revised? Parsons said Tuesday he’d be happy to raise that question with the working group.

One challenge: New conditions imposed by the state trust in charge of Pennsylvania’s allocations.

At a national level, the allowable uses for the money haven’t changed. However, the state trust has said that unless a county applies for and receives an exemption, allocations must be used within 18 months, and they can’t be used for law enforcement — a stricture that potentially precludes funding for the Drug Task Force.

That’s a significant policy change, Pfursich said. When the first phase of the settlement was being discussed, counties across the state wanted to know if money could be put toward their drug task forces, and they were assured they could by the office of then-Attorney General Josh Shapiro, who is now governor.

“It’s a little strange for them to be setting additional rules,” Parsons commented.

Commissioner John Trescot concurred. If a provision isn’t in the national opioid settlement itself, what’s the justification for imposing it, he asked.

The commissioners and Pfursich agreed to look further into why the additional rules were instituted and whether it makes sense to lobby for them to be lifted.

Inquiry may show that there’s a reasonable explanation, Pfursich said after the meeting: For example, the 18-month time limit may have to do with the national settlement’s reporting requirements.