Consultants from the Pennsylvania Economy League provided Lancaster’s Home Rule Study Commission on Thursday with an overview of the issue that prompted the commission’s empanelment in the first place: Lancaster’s structural budget deficit.

The city’s revenues and expenses are “significantly out of balance,” Fred Reddig told the commission as he went through his presentation.

He pointed to a question at the bottom of one slide: Can the city’s financial structure continue to provide for the health, safety and welfare of residents?

“That’s the fundamental question that I think you need to be looking at,” he said. Later he was more pointed: “You can’t operate the city in an unbalanced manner over the long term.”

Limited options

Under Lancaster’s existing charter, property tax increases are the only way city has to reliably grow its revenue. Under a home rule charter, it would be able to lift the current 1.1% cap on the earned income tax, or EIT, and raise more money from it.

When Mayor Danene Sorace, in her January State of the City address, called for studying home rule, the city’s fiscal straits formed the core of her case. High property taxes are burdensome, especially for low-income homeowners and those on fixed incomes. Shifting toward the EIT could alleviate the pressure on property taxes and move the city toward a more equitable and sustainable tax structure, the mayor said.

Might there be other alternatives, other means of boosting revenue? At Thursday’s meeting, in the course of an overview of Lancaster’s general fund budget, Reddig and PEL’s Gerald Cross suggested that, by and large, there aren’t.

Taxes account for 67% of city revenues, they said, and real estate taxes (the property tax and transfer tax) make up 72 cents of every $1 in taxes. Lancaster is essentially levying all the taxes it is authorized to levy; and apart from the property tax, it is at the maximum rate or amount.

Even a robust building boom has barely any effect on the real estate tax base, largely because the quantity of existing property value is so large to begin with: Since 2018, the total assessed value of property in the city has grown just 1.1%.

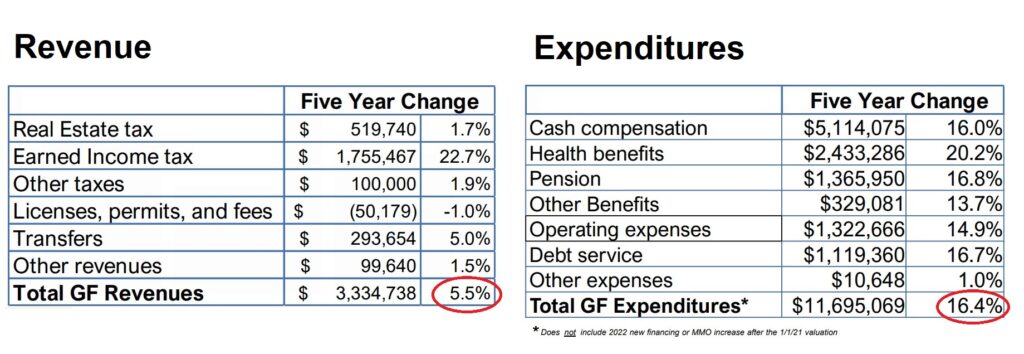

According to projections from another city consultant PFM, Lancaster’s total revenues from all sources, assuming no rate changes, are projected to grow just 5.5% over the next five years.

Driving most of that increase is a robust increase of 22.7% in revenue from the EIT. There is no rate change involved: The increase would come from underlying income growth and population growth.

On the expense side, city government’s current and legacy personnel costs — pay, benefits and pensions — account for 74% of spending. Government is a people-intensive business, Cross said: You can’t deliver services without employees.

Lancaster has sought to trim costs in various ways over the years, moving to self-funding its health insurance and hiring PFM to conduct efficiency and cost analyses. That said, the city cannot afford to cut back on services that citizens expect and deserve, including public safety, infrastructure improvements and responsive government, Sorace has said.

Over the next five years, PFM expects salaries, benefits and pensions to increase 16%, 20.2% and 16.8%, respectively, contributing the bulk of an overall 16.4% increase in city spending.

And that’s the problem: 5.5% more income doesn’t cover 16.4% more expense. Currently, Lancaster is filling the gap with reserves and American Rescue Plan Act funding. Once they’re exhausted, if the city doesn’t raise property taxes, it will have a deficit approaching $70 million by 2028, PFM projects.

Besides the general fund, Lancaster’s budget incorporates enterprise funds for water, sewer, trash & recycling and stormwater. Those are self-funding fee-for-service operations, and Reddig and Cross did not discuss them.

Market values v. assessed values

Commission members quizzed Reddig and Cross about reassessment, about the feasibility of taxing non-city residents, and about Pennsylvania’s array of special-purpose taxes, such as library, shade tree and community college taxes.

Without regular reassessment, market property values gradually diverge more and more from assessed values. In Lancaster County, which completed a reassessment in 2018, the gap is relatively small, Cross said; reassessment is a political third rail, and some counties haven’t done it in decades.

Commission member Darlene Byrd asked if the city could capitalize on gentrification. Not really, Reddig and Cross said: Extensive property improvements might trigger a reassessment, but selling a property doesn’t change its assessed value, even if the sale price is much higher.

Apart from the local services tax, imposed on taxpayers who work or do business in Lancaster, Pennsylvania provides municipalities no options for taxing non-residents, Cross and Reddig said. As for special-purpose taxes, they have to be put toward their intended purpose and can’t be used to fill a general fund deficit.

Commission member Maxine Cook asked if Lancaster’s police budget — 41% of total spending — is in line with peer municipalities. Cross affirmed that it is: The typical range is about 33% to 50%. Nor is the city’s debt service a red flag: At 8%, it is solidly in manageable territory, he said.

“You are providing an efficient and effective government,” he said. “The problem is, for how long?”

Next steps

In other business Thursday, commission members:

- Approved a set of written questions for the mayor, City Council president, controller and treasurer, to be answered within two weeks, if possible.

- Agreed to question state Reps. Mike Sturla and Ismail Smith-Wade-El and state Sen. Scott Martin about state policy and potential legislative action on municipal finance reform.

- Agreed to discuss at their next meeting on Sept. 7 the idea of holding a series of community informational and input meetings, potentially before the end of the year.