"Finding No. 2" in the housing study that was presented to Lancaster's City Council this week will come as no surprise to any local renter or would-be buyer.

"The City of Lancaster has a housing shortage," it reads.

Dig into why that shortage exists, though, and what options there are for easing it, and a nuanced picture emerges, one that delineates just how difficult a challenge the city faces.

Prepared by Naomi Young, director of the Center for Regional Analysis at the Economic Development Co. of Lancaster County, the study's findings are the basis for the city's interim housing strategy, a five-year plan to ease price pressures through a mix of new building, targeted rehabilitation efforts, regulatory adjustments and safety net enhancements.

The study can be downloaded from the city's website. Here are five takeaways from its key findings and conclusions:

• Too much X, not enough Y: Contributing to Lancaster's housing supply crunch is a mismatch between the types of housing available and today's household patterns, the report says.

Specifically, there is an oversupply of single-family dwellings: They account for 56% of city housing units, but only 30% of local households have children under 18. Moreover, around 30% of city households are single individuals. The city thus needs more one- and two-bedroom apartments, the study said.

Young told City Council she was struck by the importance of evolving household composition on affordability, saying the correlation is considerably stronger than the one between affordability and race. Households are growing smaller and female-headed households are growing more widespread, and they often struggle to find housing they can comfortably pay for, she said.

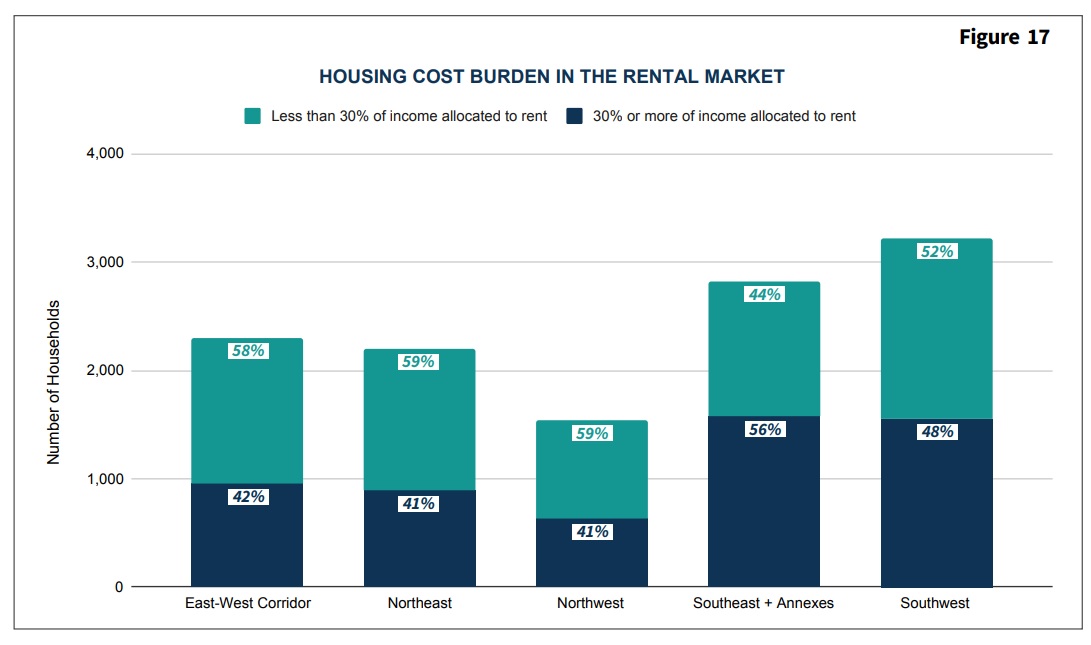

• Housing cost burdens are widespread ...: About one-third of city households and nearly half of city renters are cost-burdened, paying more than 30% of their income on rent or a mortgage. Housing costs are an issue not just for poor families, but for a wide swath of low and middle-income earners, the study said.

On balance, it said, "household incomes are not adequate to meet market rental rates."

• ... but they are worse in the Southeast and Southwest: Among renters, 56% of Southeast and 48% of Southwest households are cost-burdened, versus 41% of renters in the Northeast and Northwest. Lancaster's south side neighborhoods are home to the city's highest concentrations of poverty, the legacy of a history of racial and economic segregation.

• Opportunities to increase housing supply are limited: About 88% of city tracts (16,040 out of nearly 18,300) already have some form of housing on them.

• It would take a lot of new housing stock to move the needle: Lancaster's estimated rental and homeowner vacancy rates are under 3%, versus a "healthy" vacancy rate of 5% to 10%. The numbers suggest the city needs 1,165 to 2,455 more housing units.

Without them, the city is likely to see more displacement and fewer renovations, as landlords can rent their properties at high rates without having to improve them, the report says.

Thus, "the City needs intentionality in developing housing stock with a focus on large scale projects," it says.

What is 'affordable' housing?

Ultimately, housing affordability is an individual matter: What households can afford to pay depends on the other demands on their income.

As a rule of thumb, however, most analysts set a benchmark of 30% of gross income. Households that pay more on their rent or mortgage are considered cost-burdened; households that pay more than 50% of income on housing are considered severely cost burdened.

The flip side of the affordability discussion has to do with subsidized construction. Federal and state funds are available for housing projects that make some or all of their units "affordable."

Affordability is pegged to some percentage of "area median income" (AMI): For example, a unit might be considered affordable if someone earning 50% of AMI would pay no more than 30% on rent.

In areas with large income disparities, however, AMI calculations can still exclude many of the people affordable housing is theoretically intended to help.

In the Lancaster area, AMI is often based on the county median income, which is a little over $66,000. Median city income, however, is 31% lower. So, for a household at 50% of city AMI, an affordable rent based on county AMI would eat up, not 30% of income, but 43.5%.