(Editor’s Note: This article was researched and written by Sami Subedi as part of the Refugee Youth Journalism Project.)

When refugee families first arrive in Lancaster, one of the first things scheduled is a trip to the doctor’s office.

Years of physical trauma, poor nutrition, and lack of adequate medical care can take their toll on otherwise healthy people. Seeing a doctor is the first step in addressing any health problems that could impede thriving in the new community.

But what’s sometimes overlooked for newcomers is an awareness of the toll that forced migration and persecution take on refugees’ mental health.

Language and access to quality providers are two crucial barriers. Still, the most crucial obstacle is the stigma attached to mental health in communities like my own, the Bhutanese-Nepali community.

That stigma makes mental health a taboo topic of conversation, or worse, renders common and treatable conditions like depression and anxiety unavailable to those who could use the most help.

While overcoming those stigmas has been an uphill battle, many Bhutanese-Nepali youths are working hard to recognize and address the importance of mental health.

Forced migration

The most significant source of trauma among the Bhutanese-Nepali community is the forced migration from their home in Bhutan, a small Asian country bordering Nepal and China.

While hundreds of thousands of ethnic Nepalis lived, farmed, and held land in Bhutan, in the 1980s and early 1990s, the ruling aristocrats wanted to “purify” Bhutanese culture and began to force a “One Kingdom, One People” doctrine that prohibited Nepali language, clothing, and customs in public.

Eventually, the government grew more aggressive, pushing ethnic Nepalis off their land and using violent persecution to push Nepalis out of the country.

By 1993, over 100,000 Nepalis had been forced out of the country. Because they had been citizens of Bhutan, they were not accepted into Nepal. They had to live in refugee camps.

This direct experience of violence and persecution was traumatic for the adults who remembered life in Bhutan. Life in refugee camps left its mark on the children, who never saw their homeland.

Even though these events, not to mention sudden relocation to a new culture and home, would be traumatic for any person, there is little recognition of emotional and mental trauma in the Bhutanese community.

Nepali has no words for common mental health words like “depression,” “anxiety,” or even mental health itself. When someone does suffer from these conditions, they are often told to deal with them. Someone who sufferers from a mental disorder in this community finds it very hard to ask for help; everyone seems to despise a mentally ill person and is socially excluded. This makes the problem more significant because those who live with a mental disorder don’t know that these things can sometimes be treated easily with therapy and other healing methods.

High levels of PTSD

Dr. Yadhu Dhital is a former Nepali refugee. As an undergraduate at the University of Pittsburgh, he wanted to understand how much trauma the Pittsburgh Bhutanese-Nepali community faced and how they were dealing with mental health concerns.

His study showed that among 55 participants, 36.4% reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD. This would be very high for any population.

An individual with PTSD has difficulty recovering after experiencing or witnessing a trauma. Due to forced migration, refugees face various traumas; in former Bhutanese refugees, many experienced beatings, threats, humiliations, sleep deprivation or and social isolation.

Dhital said that when people experience mental health disorders, they are more prone to hide their symptoms and put on a happy face. They hide their symptoms from their friends and family, thinking others would talk bad about them. This way, their problem never resolves.

The effects of this trauma are even worse when they aren’t acknowledged or understood by those who have experienced them, in a culture where talking about mental troubles is taboo and where the message is “just deal with it.”

Community reaction

To understand how the Bhutanese-Nepali community in Lancaster understands mental health, I interviewed community members of different ages to see their reactions to PTSD and other issues.

I first spoke with my mother, Dil Maya Subedi, age 52. When I asked her about anxiety, depression and other mental health disorders, she said in Nepali, “I don’t know what it is.” She answered subsequent questions with the same response, saying she did not know what it was; therefore, she did not believe it was something that existed.

In a society where so many answers can be found at the touch of a Google Search button, my mother has no knowledge of mental health, let alone what the word itself means. It is shocking to see that our elders, who we learn from, are so unaware of the topic.

When I asked her what someone should do if they are going through this, and she didn’t have an answer, she said that she never knew how you named those feelings, and she had just been living with it as if its “normal.”

I also spoke with Nirmala Dhungana, 22, an accounting major at Millersville University and a member of BRIGHT, Bhutanese Refugees Inspiring, Growth, Humanity, and Traditions. (She and I are among the five founding members.)

She said our community often sees mental illness as a sign that you have no knowledge of reason and should be placed in a mental asylum.

She went on to say, “If we know someone diagnosed with a mental health disorder, we label them “boula” and look for ways to stay away from them instead of supporting them.”

The word “boula” translates to calling a person crazy. This is striking as Dhital mentioned the same thing when asked if he thought there are stigmas about mental health in Nepali communities.

Hope

This creates a generational rift between younger people and the older generation who believe mental health is something you don’t talk about and problems are something you live with.

Our younger generations are going to school and becoming more aware of these issues. They are learning about it through media and the school, making them feel more comfortable talking about issues like mental illness. This way, they can put more words to their feelings.

Many young people don’t feel like older generations understand them. Many struggle with substance abuse or suicidal thoughts. Dhital says we need “”awareness to reduce stigma,” but the question is, how can we spread that awareness in a culture like ours?

Some have suggested we need more support groups to spread awareness and create safe spaces.

As college students we BRIGHT members understand the problems of our generation and the upcoming generation. We target our younger peers to help with things like SAT prep, but also mental health.

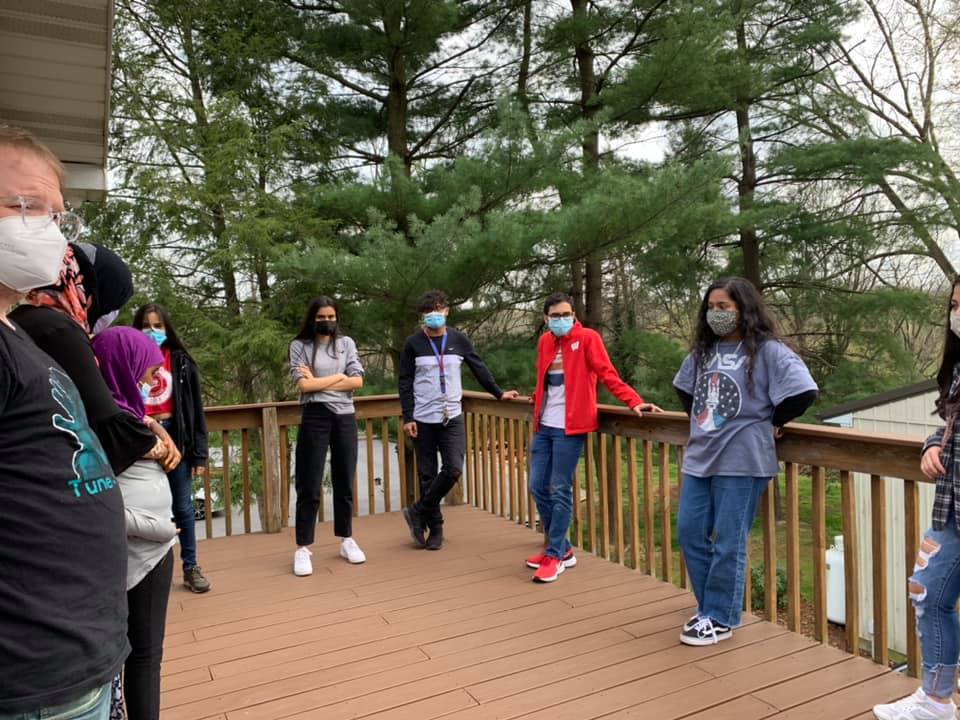

In April 2021, BRIGHT hosted a session to discuss mental health called Asha Ko Adhar, which translates to “Fountain of Hope.” We had more than 15 youth from different age groups interested in learning more and sharing their personal experience.

To get a little personal, every person in that room came with a listening ear, and the way they were able to help one another was just incredible.

This shows just how much help our community needs, especially our youth. They want to see changes, be helped, and raise awareness; but when will our elders realize that having a mental illness does not mean that you are crazy? All they need or want is an ear to listen and encourage them to get help.

BRIGHT has allowed youth to talk to their peers about the need for their mental health and those of their parents and grandparents. We strive to be the leaders that we needed when we were younger.

We want to be positive, but …

We quickly learned that our community lacks therapists and service providers who can speak Nepali or who are culturally competent enough to understand the trauma of forced migration/persecution.

Young people need help, that’s for sure, but so do our elders. They need to understand what they went through is not normal. They need to be aware of what mental health issues are, who gets them, how we can deal with them, and how we can help those around us.

To anyone old or young struggling with mental health anywhere: Know that you are not alone. You will get through this. Acknowledging that you need help is the most significant step you can take to become better. Remind yourself that “you got this,” even if the whole world wants to tell you otherwise. I believe in you, do you? — Sami Subedi

To even attempt that, we need someone who is educated in this field and understands the trauma they have faced, which we lack. Due to this specific reason, our elders have many stigmas and a lack of knowledge.

I am grateful that even though our elders have gone through all trama and issues, they are were able to sacrifice everything to give us a better chance at our future.

Now many young people see mental health issues and are working to make a difference in our community. Some are speaking up on social media, teaching parents what they are learning in schools, speaking up when stigma is brought up, and most importantly, majoring in psychology and other medical studies to help our Bhutanese Nepali community.

I am amongst the many who want to focus their study on mental health within minority communities.