Just over a year ago, in January 2023, a coalition of local nonprofits led by YWCA Lancaster released a document intended to spark discussion, reflection and change: the Lancaster County Racial Equity Profile.

Over 97 pages, it tabulated a broad array of social and economic indicators: Life expectancy, incarceration rates, poverty levels, incarceration rates, educational attainment. Wherever possible, data was broken out by race and ethnicity, often demonstrating stark disparities.

An accompanying summary called on the Lancaster County community “to boldly address racial inequities” and to make equity “a core operating principle.” By doing so, it said, the county can emerge strongly from the aftermath of the pandemic and lay the groundwork for prosperity “for generations to come.”

The profile was the first of its kind for a Pennsylvania county. Twelve months on, advocates say, it remains a living document and a focus of ongoing countywide conversations about social change.

For many people, the data has been “eye opening,” said Isabel Castillo, director of YWCA Lancaster’s Center for Racial & Gender Equity. Among the statistics drawing the most attention and concern:

- Rental cost burdens: 48% of local renters pay more than 30% of their income on housing, but that rises to 58% for people of color and 59% for Latinos.

- Child poverty: The rate is 9% for White households but 33% for Blacks and 34% for Latinos.

- Bail: Average cash bail in 2016-17 was $55,177 for White defendants but 19% higher, $66,013, for Black ones.

- Life expectancy: Average Black life expectancy is 75 years, five years lower than the average of 80 across all groups.

Castillo coordinates the Racial Equity Action Team, a group of local volunteers. Since March, they have been meeting monthly at YWCA Lancaster to explore the issues raised by the profile and potential solutions. About a dozen people attend regularly and close to 200 are on the team’s mailing list, Castillo said.

Representatives have made presentations at libraries and local businesses and are tapping into their social networks, said member Aimee Van Cleave. Last week, Van Cleave and Castillo talked about the profile on the Spark, WITF’s current affairs talk show.

Member Jill Heine said she’s new to organizing and appreciated being “warmly welcomed” by the Action Team.

“Our group functions in a way that recognizes each person’s unique contribution,” she said.

For more information

The Lancaster County Racial Equity Profile was created by the nonprofit PolicyLink and the Equity Research Institute at the University of Southern California and is part of their National Equity Atlas.

The full profile and summary document are available at the project website, equityprofilelancaster.com. The site also offers an online presentation of key indicators and ways to get involved.

United Way of Lancaster County and Lancaster County Community Foundation have both incorporated the profile into their grant processes.

Its influence is most obvious in United Way’s Level Up & Launch program, said Aiza Ashraf, director of equity & community impact.

“We specifically asked grantees to propose programs aimed at addressing the gaps identified in the Racial Equity Profile,” and the review committee weighed that factor “diligently” in making its decisions, she said. Level Up & Launch plans to take the same approach this year, too.

“We are committed to continuing to work together with our community to address the critical needs outlined in the report, and are grateful for this data as a benchmark for where we need to go,” United Way CEO Kate Zimmerman said.

One grassroots initiative that drew upon the profile was the Lancaster Justice Seekers Collective’s town hall. Held in March 2023, it convened around 100 participants who discussed the state of racial equity and ideas for advancing it.

Unfortunately, leaders could not agree on a strategy for moving forward, so it petered out, organizer John Maina said. They continue to be active on an individual basis: Maina said he plans to continue focusing his own energies on criminal justice and reducing incarceration.

Castillo said some organizations have used the profile internally to review their pay structure and human resource policies.

At the Lancaster County Community Foundation, “We use the equity lens in everything that we do,” President Sam Bressi said. While the majority of the 540-plus funds it oversees must be allocated under the terms under which they were set up, the foundation also does a certain amount of discretionary grantmaking, and equity factors prominently in those decisions.

In the coming year, Castillo said she’s looking forward to updating the data in the profile, some of which dates to well before the pandemic. She also wants to encourage organizations to report more data by race and ethnicity. When Pennsylvania, for example, releases monthly local employment data, it’s broken down by industry, by not by demographic.

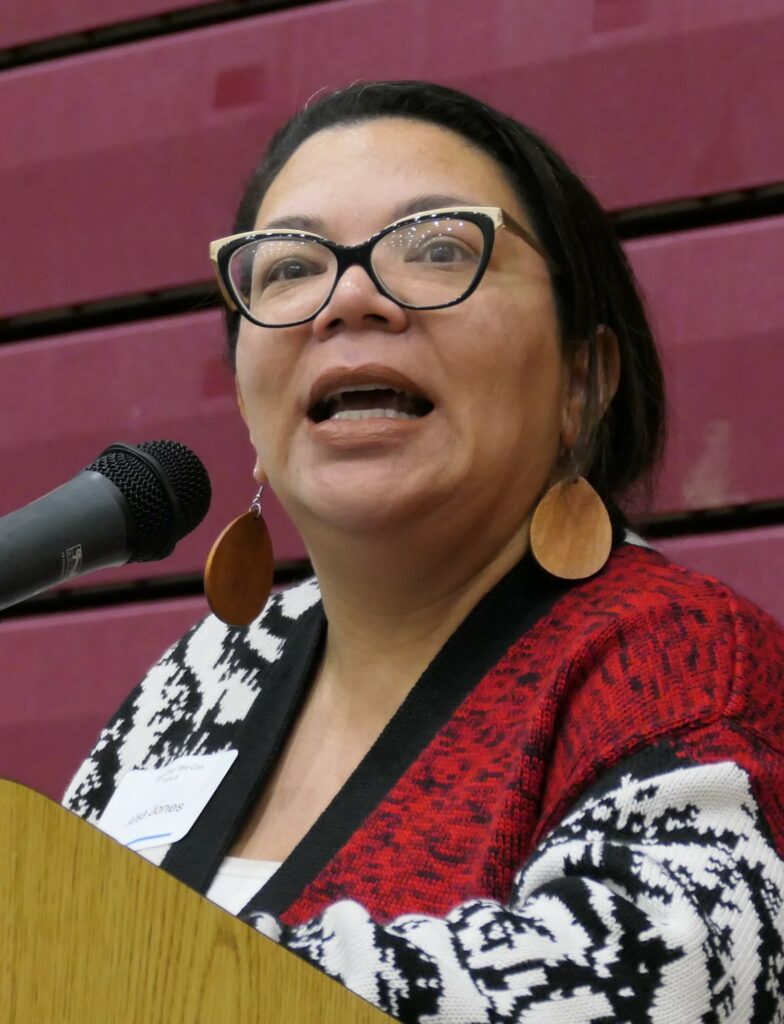

Alisa Jones, CEO of Union Community Care, agreed that expanding and updating the profile’s data is a priority.

As a federally qualified health center, Union Community Care concentrates on underserved communities, so it sees disparities first-hand. Thus, the profile catalogued “data we were already aware of,” Jones said; but publishing the information has led to “broader conversations” with people and organizations who may not have been as aware of the issues, and the opportunity for new partnerships.

As for Racial Equity Action Team, it’s looking to drill down in the coming year on one or two key indicators, Van Cleave said, and to continue building relationships with other organizations and outreach to the community at large.

The goal she said, is to go from the data to action: “from the ‘what’ to the ‘now what.'”