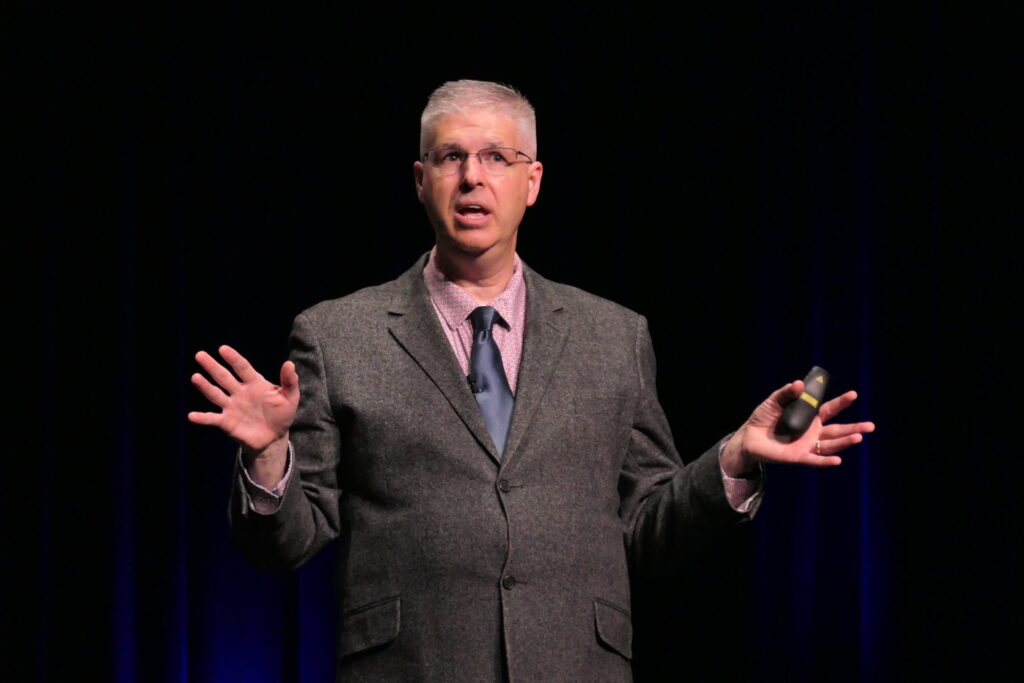

Affluent societies are willing to tolerate a lot of things that are “orderly but dumb,” Charles Marohn said toward the end of his talk Wednesday evening.

In particular, Marohn contends, communities across America are wedded to an orderly but dumb approach to planning and development that was developed in the years since World War II. As a result, they’re careening into insolvency.

To fix the problem, he counsels the opposite approach: Chaotic but smart.

“If we want to see innovation … we need to welcome and tolerate a little bit of messiness,” he said.

Marohn, an engineer by training, is the founder and president of Strong Towns, a nonprofit that advocates for urban planning practices that foster sustainable, incremental growth.

His audience at the Ware Center in downtown Lancaster included many local officials, nonprofit administrators and community leaders. Marohn presented them the core Strong Towns ideas, diagnosing the wrong turn he believes America took in the postwar decades, and offering his prescription for restoring fiscal health.

The suburban experiment

Marohn previously spoke in Lancaster a decade ago. His visit this time was organized by the Hourglass Foundation, with support from the Martin-Harinish Foundation and other organizations.

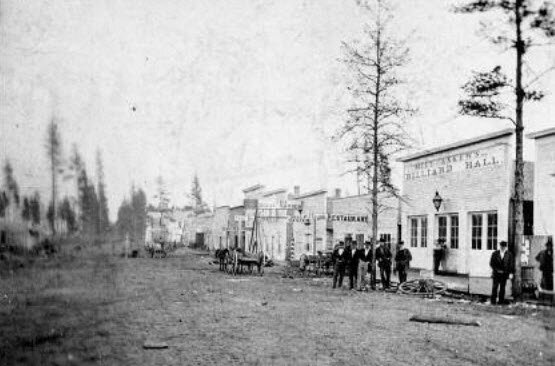

Until World War II, Marohn said, U.S. cities developed incrementally as “a series of little bets.” His hometown, Brainerd, began as a few ramshackle wooden buildings along a muddy road. As it prospered, land values in the city center increased, leading to development of more substantial buildings; meanwhile, around the periphery, a fresh generation of ramshackle shacks appeared. Lather, rinse, repeat.

“Start with a pop-up shack and eventually get to Manhattan,” Marohn writes in his book “Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity.”

These three images show the gradual evolution of Brainerd, Minnesota, from 1871, left, to 1894, center, to the 1930s. Click each image to enlarge. (Source: Strong Towns)

Incremental change is a characteristic of complex adaptive systems, and it makes them resilient, he said. But today’s development style isn’t complex, he said: It’s complicated, and that makes it fragile.

The change began with the Great Depression. It upended the economy, causing massive, widespread suffering, and for people at the time, there was no end in sight. It wasn’t until World War II solved the problem (though, as Marohn pointed out, calling a world war a “solution” to anything only makes sense if you’re an economist.)

As the war wound down and Americans demobilized, economists reasonably feared that the massive drop in demand caused by disarmament and the increase in the labor force from returning GIs would unleash a new depression. So, the federal government set out to expand and sustain demand, using all the means at its disposal: Funding the interstate highway system, supporting homebuilding and using interest rate cuts and deficit spending to maintain full employment.

The goal was to turn cities into “kinetic growth machines,” Marohn said. “Here’s the amazing thing. It worked.”

It did so, however, by decoupling growth from the local wealth available to sustain it over the long term. The result, Marohn says, is “the Suburban Experiment,” aka “the Suburban Ponzi Scheme”: A development pattern characterized by huge infrastructure buildouts that initially yield financial windfalls, but that require ongoing maintenance costs that cannot possibly be covered by the revenue from the residences and businesses they serve.

The system produces large economic flows, but doesn’t support wealth creation, Marohn said. Family income grew about 1.6 times between 1950 and 2015, he said, but families are living in municipalities with liabilities that have grown tenfold or twentyfold.

Does Lancaster fit the Strong Towns narrative?

Much of suburban Lancaster County reflects the development patterns that Strong Towns founder Charles Marohn criticizes in his books and on the organization’s website. But how well does the “Strong Towns” story apply to Lancaster city?

It certainly faces infrastructure challenges: It has an aging sewer system in which both stormwater and sewage flow through the same pipes, and it is under a federal order to make improvements costing millions of dollars. It’s also in the middle of building a water main to supplement an existing one that dates to the 1950s.

Those costs, however, don’t necessarily relate to suburban sprawl (although the city water system serves a large number of suburban customers, and the sewer system serves a few). The combined sewer system was built out before World War II; the modern extensions have seperate pipes for sewage and stormwater.

Nor are they what’s driving the city’s structural deficit. Water, sewer and stormwater revenues and expenses flow through their own dedicated funds, not the city’s general fund.

Rather, Mayor Danene Sorace and other city officials attribute the city’s structural deficit to the state’s outdated municipal finance system. Cities must raise most of their revenue from taxes on property value, which in built-out municipalities like Lancaster increase minimally from year to year, but their expenses tend to rise in line with inflation.

The bulk of Lancaster’s general fund spending goes toward police and fire protection, which together account for about 60% of the budget.

City officials did not reply to a request for comment for this story.

Diet & exercise for cities

What should communities do? Marohn said when he first visited Lancaster a decade ago, he didn’t have much of a solution beyond “stop doing stupid stuff.” Today, he said, he has a more developed set of recommendations, which he characterized as “diet and exercise for cities.”

In general, the idea is to change policy to allow incremental, bottom-up development again. City zoning and building codes create barriers to entry that small-scale entrepreneurs can’t overcome, he said: So, lower them.

With regard to infrastructure, “Don’t build another foot of anything,” he said. If you can’t afford to maintain the roads and sewers you have now, the last thing you need is more.

Key points

- Pennsylvania’s legislature hasn’t comprehensively updated the Election Code since 1937. So the officials who run elections must rely on an amalgamation of sources outside of the text of the code itself, including recent legal opinions and advice from county solicitors, other administrators, and the state.

- Entire sections of the code are no longer in use, including directions on operating obsolete lever voting machines and language regulating the use of lanterns to light polling places.

- The legislature has not regularly incorporated new case law into the code, which leaves inaccurate vestiges. For instance, a rule limiting felons’ ability to vote remains on the books, despite being found unconstitutional.

- Newer election provisions and old code language conflict, causing confusion, lawsuits, and creating a patchwork of administration practices.

He advocates a four-step “public investment process” that starts small and addresses identified needs. With that approach, you can make a lot of mistakes and still come out ahead.

As long as a building is basically safe, let a business open there, even if everything isn’t fully up to code. Code officers and business owners can agree on prioritized to-do lists, he suggested; the improvements can be achieved over time, and allowing the business to have a revenue stream in the meantime makes it affordable to do them.

Lancaster city is well positioned to follow the Strong Towns approach, Marohn said. In general, it’s already built along prewar lines: Just “lean in” to the strengths that are here already, he said.