Everyone should be able to afford a decent place to live, but the sheer shortage of moderately priced housing in Lancaster County, whether for rent or sale, and the financial and regulatory challenges of building new stock are formidable obstacles to achieving that goal, representatives of three local nonprofits said this week.

Family Services Manager Allyson Davis of Lancaster-Lebanon Habitat for Humanity, President Jose Lopez of the Spanish American Civic Association and CEO Shelby Nauman of Tenfold discussed the exceptionally tight post-pandemic housing market and the work their organizations are doing in an online panel discussion on affordable home ownership Monday evening, sponsored by the Parish Resource Center. (The forum can be viewed on YouTube here.)

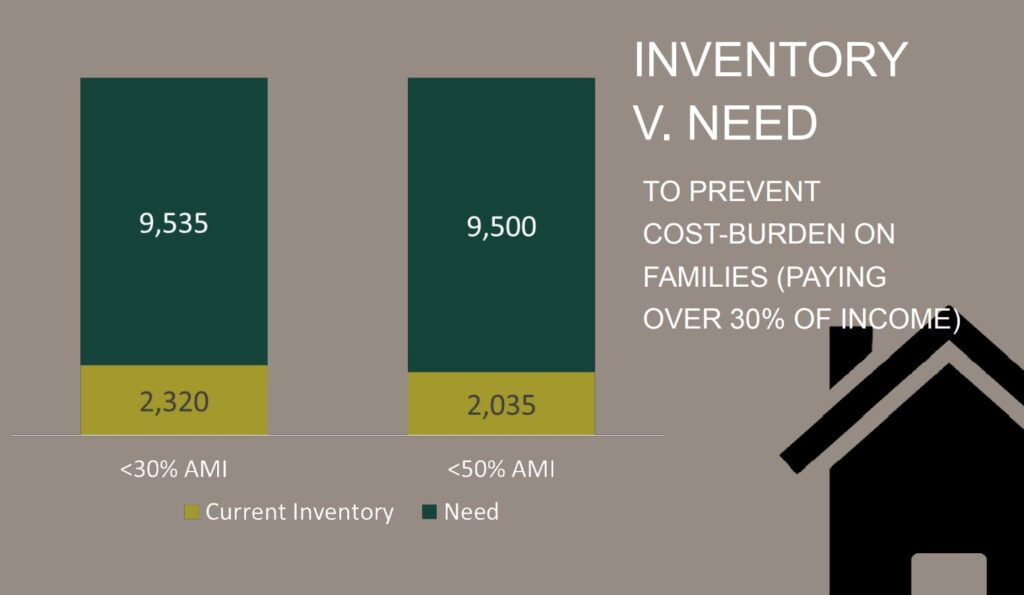

The local housing shortage, like the national one, has been an ongoing topic of concern. Research by the Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania and the Lancaster County Redevelopment Authority indicate Lancaster County has a shortage of nearly 20,000 homes affordable for households earning less than half of county median income. For a family of four, that’s no more than $41,500, according to federal data.

A 2021 study commissioned by City Hall found a significant mismatch between available housing types and household sizes, with too many units suitable for large families and not enough for small ones. The study author, the Center for Regional Analysis at the Economic Development Company of Lancaster County, is following up with an analysis of conditions countywide, which is expected to be released soon, Nauman said.

Over the past three and a half decades, SACA has built more than 70 affordable townhouses and rehabilitated roughly 130 blighted houses for resale. Homeownership not only promotes wealth-building for families but helps to stabilize neighborhoods, Lopez said.

Historically, redlining and other policies blocked access to those wealth-building opportunities for earlier generations of communities of color and women, Davis said, so it’s essential for today’s initiatives to prioritize social justice.

SACA receives subsidies for its townhouses so it can sell them below their construction cost, keeping them affordable. The gap is significant: It’s costing about $350,000 per unit to build the nine townhouses now under construction at Conestoga North, Lopez said, but they will be sold for no more than $180,000, or just over half price. Some will be sold for even less.

Habitat for Humanity uses volunteer labor for much of its projects, which helps keep costs down. But there aren’t many properties left to rehabilitate in Lancaster, and developers are eager to snap up the ones that are left, Davis said, with even badly deteriorated properties sometimes selling for $80,000 or $90,000. That leaves little opportunity for nonprofit developers, she said.

City government has the power to condemn blighted properties and resell them through its redevelopment authority and Land Bank. The Land Bank has a policy to give affordable-housing nonprofits the first chance at acquiring its properties; the idea has been floated of implementing a similar policy at the redevelopment authority, and Lopez said he hopes it happens.

Outside the city, jurisdictions tend to have large minimum lot sizes and other zoning and land-use restrictions that make affordable housing difficult or impossible to build.

Stable housing is the foundation for stable lives, and people can’t thrive without it, Nauman said. Moreover, she added, the scale of homelessness in Lancaster County is far less daunting than in places like San Francisco. Solving it here is “completely doable,” she said.