“I grew up as a ‘P.K.,'” says the Rev. Louis Butcher Jr.

“P.K.” stands for “preacher’s kid.” Butcher’s father was a pastor for nearly 40 years at a small church in Conoy Township and he wanted Butcher to follow in his footsteps.

Related: Local Black leaders reflect on Juneteenth

Eventually, Butcher did, but as a young man he wanted to stretch his wings. So, after graduating from Franklin & Marshall College in 1965, he pursued a business career with the Hamilton Watch Co. and then the John Wanamaker Department Store, roles that took him to Philadelphia, Reading and New York.

Eventually, he returned to Lancaster, where he became executive director of the Lancaster County Human Relations Commission. He remained there nearly two decades, stepping down a few years before the commission was disbanded.

In 1980 he spearheaded the foundation of Bright Side Baptist Church. The church and its sister entity, Bright Side Opportunities Center, have grown to become beloved community institutions, offering spiritual guidance, fellowship and a wealth of social services.

Butcher, now 79, retired five years ago this month. Despite deteriorating eyesight that has rendered him legally blind, he stays active. He operates WLAB 107.3, an Internet-based gospel radio station, and is launching a second station this month, Spotlight on Lancaster Radio.

He’s part of the 7th Ward Oral History Project and the committee organizing the 7th Ward Homecoming Weekend, a reunion planned for late August.

Butcher recently shared his thoughts with One United Lancaster on growing up before the Civil Rights era and the changes he has seen since then; his experiences launching a church and the challenges facing the Black community today.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

On ‘de facto segregation’

Butcher: We lived in the Seventh Ward of Lancaster, as did just about all African Americans then. The Seventh Ward was multi-ethnic, multicultural over the years. It was Jewish, Italian and German, then it became primarily African American; and after that, right now, primarily Latino.

As a kid, I experienced de facto segregation. Of course, segregation was not legal, but trying to escape the Seventh Ward if one wanted to was virtually impossible.

Even within the Seventh Ward, there were areas that discriminated against Black people. If there was a house for rent on South Lime Street, for instance, the practice was that you called the landlord and asked, “Do you rent to colored?” If they said no, there was no protest. You’d just move on to the next listing. That was pretty common.

In the Eighth Ward up on Manor Street, there was a movie theater called the Strand, and the Strand did not cater to Black people. My mother and my aunt had been World War II volunteers for the Red Cross. The Red Cross had a celebration at the Strand and when they went to go in, they were not permitted. …

A number of the swimming pools in Lancaster [were segregated]: One at Rocky Springs, one at Maple Grove. There was one called Brookside out on Harrisburg Pike.

I carried newspapers, and when the paperboys’ picnic was held at Rocky Springs, management said I could get more tickets to ride the amusements if I would not try to get into the pool. My mother was very upset about that. She pulled me out of the park and took me home.

As seniors after our prom, we all went over to Mount Gretna Pool in Lebanon County the next day. When I and my prom date got there, some of the guys were already there. The manager was very embarrassed and apologetic but he said my date and I could not come into the pool. I said, “Why?” He said, “Because you’re negros and we don’t allow them in.”

When the guys saw me standing outside, they said, “Hey, Lou, come on, what are you waiting for?” I said, “I can’t come in,” and I will say to their credit, all of them came out of the pool. They came outside and said, “If Lou can’t swim, none of us will.”

Conditions began to change in the 1950s, Butcher said. One important impetus: World War II. Black soldiers had fought overseas for freedom and democracy and were no longer willing to have their rights ignored when they returned home.

In 1954, the Brown vs. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, declared segregated schools unconstitutional. By the 1960s, there were demonstrations around the country, including in Lancaster.

Local companies began to broaden their hiring beyond White applicants. As they did, Butcher became involved in an initiative to coach Blacks on the firms’ entrance exams. A lot of people, especially older ones, felt intimidated by them, he said.

Butcher: People started wanting to move out of the Seventh Ward. There was a fair housing group that would show a white face to a potential landlord or to a realtor. Once the property was rented, then a black family was put in, but that was the only way.

There was a family that had grown up in the southeast and wanted to move over into the Eighth Ward on Union Street. The realtor and the seller refused to sell them the house, and they took it to the state Human Relations Commission. They brought suit and the family was allowed to buy the house. That kind of started opening up the housing opportunities in the city and eventually into the county.

On Lancaster in the old days

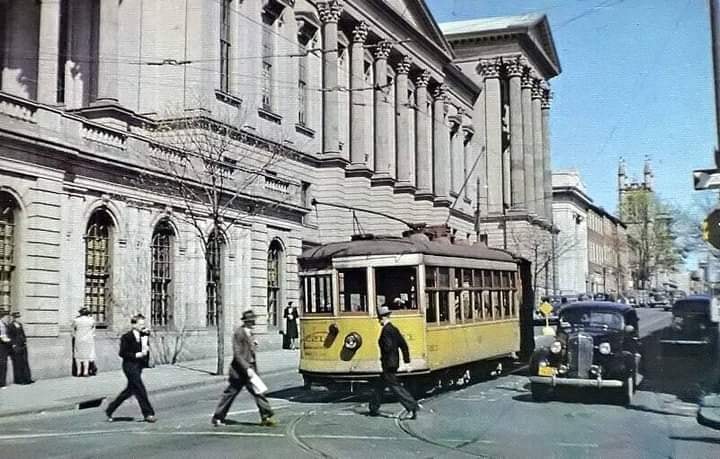

Butcher: When I was a kid, there were real trolleys, trolleys on tracks, all through Lancaster city. As a matter of fact, it was an extensive line. One of the popular lines was from Lancaster to Hershey Park. But if you were patient, by changing from one line to another, you could actually ride the trolley to Philadelphia.

The CTC was the Conestoga Traction Company and they evolved into the Conestoga Transportation Co. One of the popular destinations was down Duke Street to Rocky Springs Park.

Since Black children weren’t allowed to swim in the pools around Lancaster, they swam in the Conestoga River. One spot was behind Conestoga View, known as the “pogey,” a slang word for “poorhouse,” as Conestoga View was known as the time. The other spot was down by the waterworks.

Butcher: It was dangerous. I know we lost at least one kid in the pogey, and there may have been more. But if you wanted to swim, that’s where you had to go.

On becoming a minister

Butcher: I had a scholarship to seminary when I graduated from F&M but I really wanted to see the world. So I went out into business. But later on, I felt a calling to go into ministry. And so I became a minister under pastor McMorris at Ebenezer Church in Lancaster.

When Butcher was working in New York, his father-in-law began encouraging him to return to Lancaster to start a church. Butcher did so, arranging with his firm to be transferred to a job in Reading. In July 1980, Bright Side was launched.

Butcher: The first service, I don’t know, maybe 25 people came. We took an offering and it was $57. We had our first meeting the next Thursday and five people — I was the sixth — signed on to be a part of Bright Side Church, which became a mission and then the church.

After a month, the small Missionary Baptist congregation started looking for a venue. Bright Side’s first location was a converted dance hall on the first block of South Prince Street. From there, it moved to 215 S. Queen St., its home for 22 years.

Growing the church

Butcher: By the time we outgrew 215 S. Queen St., we were up to three services a day. It was very taxing, but we had to do it because the building was overflowing. We had a good solid youth program and a solid senior citizens’ program.

We wanted to move, but we couldn’t find a place. Eventually, we were able to secure the 500 block of Hershey Avenue.

Before that, Bright Side had purchased property on Locust Street. That site proved to be too small for a church, so instead it became home to Bright Side Corners, an eight-unit affordable housing development.

Butcher: When we got ready to go to Hershey Avenue, we did a community needs assessment. And people said, “You know, this is what we think we need.” Then some nonprofits came and said, “You know, we don’t do service provision in that area. Can we partner with you?”

When we looked at what they wanted to do, plus what we wanted to do, it could not have been done within the church building (that was being planned). So, we said, “We have to build a separate community center beside the church.” …

Bright Side’s leaders realized it would cost less to build two buildings at the same time rather than sequentially, but a capital campaign would be needed to do so.

Butcher: We hired a fundraising consultant. We told them what we wanted to build … and they said, “OK, let’s see what you have to be able to do a campaign. Do you have any students?” We said no. “Alums?” No. “Any parents?” No. “Any prior major donors?” No. And they said, “OK, you have nothing to start a campaign with.”

They were skeptical, so they said, “Give us $20,000 and we’ll do a feasibility study and tell you if you can raise any money.” And they came back and said, “Well, to our surprise, people do know you. They know your church. They think you can probably raise $3 million, though it may take a little bit longer than a traditional campaign.”

We said, “Let’s do it.”

In September 2004 the new Bright Side Baptist Church opened, followed by Bright Side Opportunities Center in November. The complex cost about $7.5 million — a remarkable achievement for an organization that began with $57.

Butcher: Once I asked one of my friends for a donation, which he gave. He said, “By the way, I’m adding $57 to it, because I’m tired of hearing you talk about it. Now you got your 57 bucks. Now shut up!”

Then and now

Butcher: Things are better today, but there are still challenges. The challenges right now are not so much segregation as economic.

There are still very few very few industrial firms owned by African Americans, very few businesses. One of the goals that the older generation is trying to instill in the young people is to try to take advantage of what’s out there and excel, understanding that it takes hard work.

With the economy the way it is with inflation and supply chain shortages and all of that, starting and maintaining a business is a lot more challenging, but it still can be done. …

I think young people of all ethnicities ought to understand that you have worth. It hurts me when young Black kids will kill each other. It’s so unnecessary.

Some of the things that are going on now in our country — it’s sad. But I have faith that this is a strong nation. We should be capable of working through our problems.

I worry about our young people because so many things are different now. I think technology is a two-edged sword. It can be used very, very beneficially. But it can also be used detrimentally.

I think the same goes with social media. These are all things that young people today have to cope with, that our generation did not.