The massive influx of federal aid during the Covid-19 pandemic helped thousands of families in Lancaster County keep a roof over their heads and food on the table, a group of local panelists said Tuesday.

But much of that aid has expired, and the rest of it is scheduled to follow suit. Food pantries and other social service agencies say they have already seen demand swell as a result, and they’re worried about what lies down the road.

“We are transitioning from a pandemic crisis to a hunger crisis,” said Brad Peterson, executive director of Power Packs, quoting a comment made last month by Vince Hall of Feeding America.

“We’re all sitting on the deck of the Titanic as that iceberg is coming in,” said Phil Falvo, public policy director of United Way of Pennsylvania.

Peterson and Falvo were two of the five panelists in United Way of Lancaster County’s online “Conversation About OUR Community” on food security. Joined by Mary Beth Williams, vice president for student affairs at Millersville University, Zach Zook, senior policy research manager at the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank, and Sandra Valdez chief operating officer at the Spanish American Civic Association, SACA, they discussed food access within the larger context of the challenges facing lower-income working households. United Way of Lancaster County President and CEO Kevin Ressler moderated the forum.

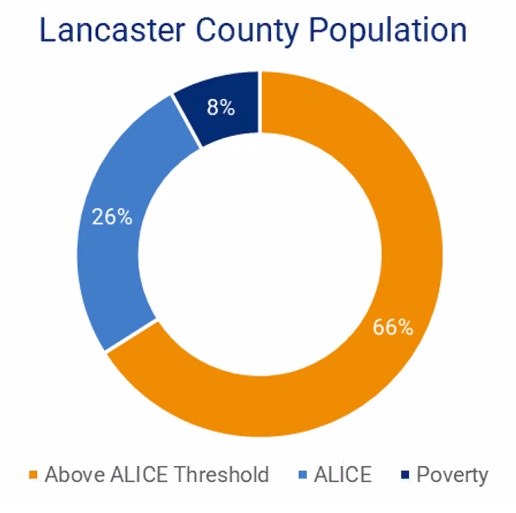

The challenges are summarized in United Way of Pennsylvania’s ALICE data, which Falvo presented to kick off the conversation. ALICE stands for “Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed”; ALICE households earn more than the federal poverty level but still struggle to cover housing, food, healthcare and childcare costs.

In all, about 34% of Lancaster County households fall below the ALICE threshold, according to United Way’s data. Its most recent report is from 2020. An update, with post-pandemic data, is due in early May, but for the ALICE population, “not much has changed,” Falvo said.

Without the pandemic aid of the past three years, he emphasized, “ALICE households would not have made it.”

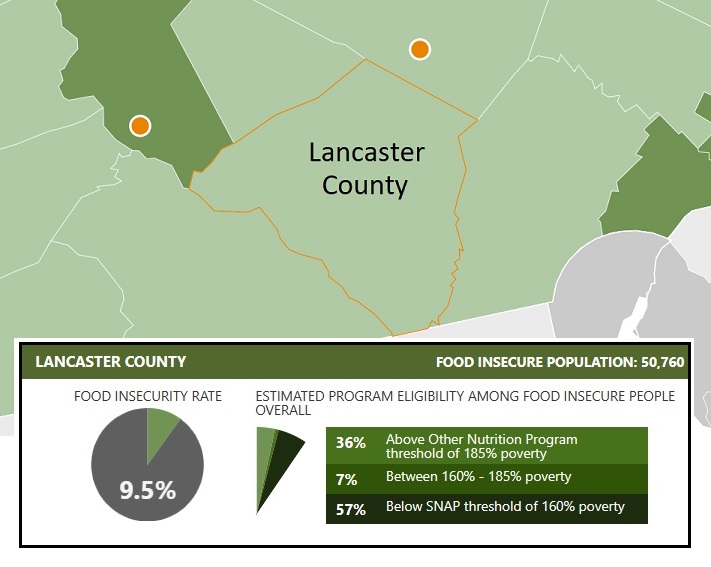

Roughly 9% of Lancaster County households are food-insecure, Zook said. That’s a little lower than the 10% to 11% average nationally, but it’s been hard to drive those numbers lower, he said.

Food insecurity among Black and Latino households in Lancaster County is 21%, versus 6% for Whites, and children are 55% more likely to be food-insecure than older age ranges, he said.

In February, the extra payments provided to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program beneficiaries during the pandemic ended, reducing monthly SNAP benefits by a little over $100 per person in Lancaster County. In the weeks since, demand in the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank’s network has steadily increased, Zook said.

Power Packs has seen the same increase, Peterson said. The nonprofit provides weekly food packages to families with school-age children in 15 school districts in Lancaster, Lebanon and York counties, serving about 1,300 households. The packages come with a recipe and the ingredients to make it, something other programs generally don’t do.

That element of education is important, panelists agreed: Individuals from different cultures may be unfamiliar with particular foods and how to prepare them. They also highlighted the need to be aware of potential barriers: Individuals may lack transportation, seniors may not be able to lift heavy packages, a household may lack simple utensils such as a can opener.

Inflation is straining household budgets, leading more families to turn to programs like Power Packs, but it’s a challenge for charity providers, too. Peterson said Power Packs’ unit cost is up 25%, from about $8 to $10 per pack or more. Between that and the increase in client numbers, the organization is currently running a deficit, he said.

SACA provides free in-person meals Monday through Saturday, and seniors can receive pre-packed meals to eat at home over the weekend, Valdez said. As needed, SACA connects those individuals to other services, whether in-house or through referrals to other agencies.

“Housing, transportation, childcare: All these are essential needs for all of our clients,” she said.

Millersville University is part of Pennsylvania’s Hunger Free Campus initiative and partners with the Hub, a local nonprofit, to serve food-insecure students. Contrary to college-student stereotypes, Millersville is serving a young adult population that is financially precarious, Williams said: The average student age is 27, more than half are Pell grant recipients and 36.5% are food-insecure, she said.

How can the community help? Through volunteering, financial support and advocacy for programs that help ordinary people, panelists said.

“Everybody in our economy is essential to it, no matter what role they play,” Falvo said. He expressed hope that Pennsylvania’s upcoming 2023-24 state budget will include more funding to mitigate the expected impact as the remaining federal pandemic programs expire.

Peterson said he hopes that no child ever goes hungry.

“We’re just trying to change families’ meal patterns and make a difference in a child’s life, one meal at a time,” he said.