We all want lower rates of recidivism, Scott Theurer said. We all want people released from prison to be law-abiding and to avoid re-offending.

“So how do we do that? I believe we do that through restored lives,” he said.

But that’s easier said than done for reentrants grappling with poverty, mental illness, addiction and other challenges. Moreover, there are systemic barriers that further complicate the efforts of formerly incarcerated individuals to achieve stability.

Theurer was among the panelists in an online forum on reentry Tuesday morning, hosted by United Way of Lancaster County as part of its series “Conversations About OUR Community.”

They spoke both about the practical challenges of reentry — housing, jobs and so forth — and the psychological ones: Overcoming internalized stigma, forging positive relationships and breaking free of negative ones, maintaining hope.

Today, Theurer is a certified recovery specialist and the director of recovery environments at R3House, which provides sober living environments in the Lancaster area. He is a member of the Lancaster County Reentry Coalition, which works to build capacity and coordinate services to maximize reentrants’ chances for successful reintegration into the community.

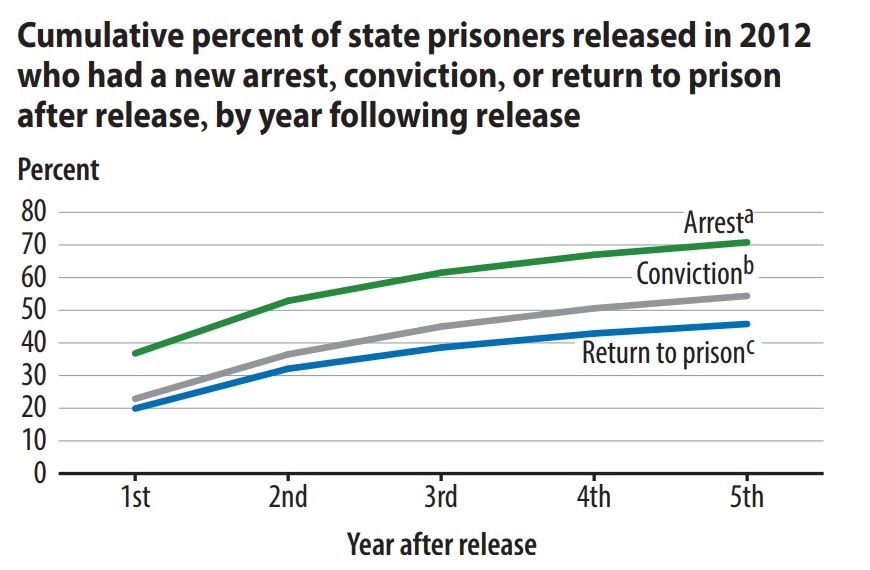

The population of reentrants is large: U.S. incarceration and recidivism rates are both exceptionally high by world standards. Nationwide, the U.S. imprisons about 530 people per 100,000 population (down from more than 750 per 100,000 in 2008). About 70% of people released from U.S. prisons are rearrested within five years.

Pennsylvania’s state prison incarceration rate is a little under 300 per 100,000; its 3-year recidivism rate is 64%.

Christina Fleugel is the reentry manager at Lancaster County Prison. The prison offers a range of resources to prepare inmates for release, including the New Beginnings class, which also provides post-reentry support.

The two-week class is “very, very intense,” Theurer said. Then comes the hard part: Exiting prison and applying those lessons in real life.

Theurer said one person told him reentry felt like walking from an air-conditioned room into a blast of August heat. Theurer said he understands: He is in recovery as a former addict and was a reentrant himself.

Of the 231 reentrants who have completed New Beginnings to date, 47 have reached the three-year mark, and their recidivism rate is 59.6%. At 90 days, the rate is 9.7%.

Christine Harrison-Mahrer is reentry manager at Lancaster County’s CareerLink office. Employment is a big hurdle for reentrants, she said, and it’s complicated further by other factors.

“Transportation is huge,” she said. “I would say that housing is even bigger.”

Reentrants frequently lack the digital literacy to apply for jobs online. Moreover, they may not understand their own legal status clearly enough to fill out employment forms correctly.

“Some don’t know the difference between an arrest and a conviction,” Harrison Mahrer said. An employer may not realize a mistaken answer was offered in good faith, instead viewing it as a lie, likely closing off that job opportunity.

Julie Kennedy, associate director of community initiatives, United Way of Lancaster County, ended up in county prisons several times before successfully overcoming addiction. For her, community service was a chance to build a resume and demonstrate to employers that she was now someone who was hardworking, reliable and trustworthy.

“Community service should be taken as an opportunity for you to connect, (to) network,” she said. “Treat it like a job, a job interview on site.”

Ron Ashby works with Returning Citizens Group. Meetings are led by formerly incarcerated individuals and participants can attend for as long as they want. New reentrants are encouraged when they see people who have been on the outside successfully for years, he said.

All the panelists stressed the importance of hope, especially Theurer and Kennedy. Kennedy said she meets with women in at Lancaster County Prison who have lost hope. She said she tells them: “I am exactly like you. … The only thing that separates us right now is that I didn’t give up.”

Many reentrants don’t understand the mental health or addiction issues that they’re dealing with, Theurer said. They need that education, as do their families and the community at large, he said.

The panelists suggested several reforms that they believe would enhance reentrants’ chance of success. It’s counterproductive, they said, for those released on parole or probation to be rearrested for minor technical violations such as missing a scheduled appointment.

Similarly, when people can’t get to work without a car, suspending their driver’s license isn’t helpful. Restrictions on relocating often return reentrants to the same environment and network of relationships that led them into criminality.

Further expanding diversion programs would better serve the many people whose criminal behavior stems from mental health or addiction problems. Having more housing available would make it easier for reentrants to being building stability.

“I’m not saying every single reentrant is ready to hit the ground running and be a productive member of society,” Harrison-Mahrer said. “But the majority of them are, and they’re just not given that chance.”