Danielle Keperling, executive director at the Historical Preservation Trust of Lancaster County, has been involved in the work of restoring historic buildings in Lancaster County since she was a little girl.

In celebration of May being National Preservation Month, Keperling sat down with One United Lancaster to talk about what the Trust does, how daytime TV launched her career path and one historical building she took to Facebook to save.

One United Lancaster: Tell me a little bit about yourself, Danielle.

Danielle Keperling: I've worked in preservation for about 21 years and my background is in preservation construction. So I'm part-time at the Trust and in my other life, my husband and I — and my parents before they retired — restore 18th, 19th and early 20th century buildings. After my parents retired, I started doing some consulting and one of my clients was the Preservation Trust.

I was their preservation consultant for about two years and then, last August, the board asked me if I would become the executive director. They had been without one for a while and I really enjoyed the work that I was doing and supported the mission, so I thought it was a really good fit.

OUL: Can you tell me more about the Trust and its history?

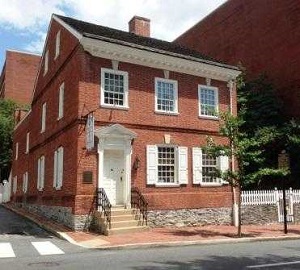

Keperling: The Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County began in the late '60s as a response to the urban development that was happening in the city. The house that we're headquartered in was threatened with demolition to build the Prince Street Garage and some community members got together to save the building.

They got it listed on the National Register, which really doesn't give it protection, but it was recognition that it was special. Actually looking at the pictures of what the building looked like, it didn't look special, but it has ties to national history. It's also a really good example of Federal-style architecture in the city and the interior woodwork is exceptional. It's very high style for Lancaster and that time period in general.

It's probably more Philadelphia-style, but the person who built the house was a joiner and so he was highlighting his craft. Some of it has been reproduced, but the majority of the woodwork was at least based off of the original.

OUL: What about the preservation work you do with your family? Tell me a little about that.

Keperling: We're contractors; we restore buildings from the 18th to early 20th centuries for both public and private clients. Probably the most famous project we've been involved with was the Petersen House in Washington, D.C.; that's the house across from Ford's Theatre that President Lincoln died in. We did the interior and exterior woodwork restoration and that was all done in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.

The one thing that's a little bit different than my work at the Trust is being able to take a project from start to finish and see the transformation.

OUL: How did your interest in preservation begin?

Keperling: All throughout high school I was going to be a social worker. Then, my senior year, my wisdom teeth were infected and I was sick for maybe four months and I think I missed 20 days of school. So I was home watching daytime TV and I saw this commercial for becoming a pastry chef and there were pretty pictures of pastries and I was like, "That's what I want to do!" So I went to culinary arts school for two years and I worked in a bakery for a few years.

I grew up in construction and preservation because that's the work my dad did but I never thought about doing it. My husband started working with my dad and I was working in a bakery and one day I'm talking to my parents and my dad is like, "I've been waiting for this moment, come work with us!" I kind of started out as a glorified secretary and I went back to school and started learning as much as I could.

But even thinking back to senior year of high school, my class schedules kind of gave a glimpse of what I was interested in because all of my classes were social studies or history classes, besides what I was required to take. So that kind of gave a glimpse, but I wasn't thinking that strategically at that point.

OUL: What does your day-to-day work look like?

Keperling: It depends on what we're doing; it varies a lot. Oftentimes, with my work with the Trust, I'm fielding phone calls, like somebody will call and wonder if they can do something with their house.

A lot of people have the misconception that we can enforce rules and I have to tell them, "We don't have any rules, but I can tell you what I would do." Some people will wonder about contractors or because they see something in their neighborhood or hear that a building is in danger.

I spend time researching ordinances and seeing what's allowed to be able to communicate with the townships because that's where enforcement is in preservation. If the building is going to be saved and the owner doesn't want to save it, the enforcement's in the township ordinances.

I also help with the marketing and strategic planning [of the Trust] and developing educational programs that help people understand what preservation is and that some of them are preservationists and don't even know it.

OUL: With that in mind, would you say that your role/the role of the Trust is more like advocating at City Council meetings and that kind of thing?

Keperling: Some of it is behind the scenes or reaching out to whoever is behind a building in danger. A lot of our work is saying, "We know you're developing this; what's your plan? Do you have a plan for the historic structure? If you don't, can we help you figure something out before it gets to the point where it's being demolished?"

There are some municipalities that are really good and they'll reach out to us regularly and ask for our feedback, and then there's municipalities that have good ordinances but aren't enforcing them. So those ones we try to reach out and say, "Hey, can we have a conversation? I know you're trying to protect your tax base, but can we protect the historic resources, too?"

OUL: What kind of laws and ordinances are in place to preserve older buildings in Lancaster County?

Keperling: It kind of depends because we have over 60 municipalities and every one gets to write their own ordinance, so it's really patchwork.

Lancaster city, Strasburg and Columbia actually have historic districts where there are rules and regulations that are pretty well set. The other ones usually have a historic resource section [in their laws] that define what a historic resource is and gives ways that those buildings can be used or steps that have to be taken for them to be demolished.

A lot of [the municipalities] do rely on the National Register listings, eligibility for the National Register or the countywide surveys that we have in our archives.

Then there are some municipalities that don't have anything. They don't have any reviews and you can demolish whatever you want. Those are the townships that I'd really like to work with; even just a 30 day review of projects to see if we can find a solution.

When I talk to people about preservation, I'm just like, "It's all local. If you care about preservation in your community, you need to attend your local meetings and make sure you're electing people that will support preservation."

OUL: How many people are on staff at the Trust?

Keperling: Just one other person, but we have a lot of volunteers. So for the walking tours we have about 50, but then depending on what projects we're working on, we'll pull other people in.

OUL: You mentioned to me before that you're mostly still working from home. How does that impact the work that you do?

Keperling: It really didn't change a lot for me in the pandemic because before I was just consulting, so I never had an office. But it is a little bit of juggling because all of the records are here, so I have to make trips to come in if someone asks for information about a property or something.

But it's doable and easy and we're starting to get back into in-person events, which is nice.

OUL: What kind of things are coming up?

Keperling: In the fall we have a preservation summit, which is bringing the municipalities and the historical societies together to talk about ways that we can help them but also why preservation is important for communities.

Then in October, we're doing an architectural history tour, which we usually do every other year, but we skipped last year.

OUL: Are those open to the public?

Keperling: They are, though I guess maybe not the Preservation Summit because that's more focused on the municipalities and the preservation societies. But we're not limiting who the societies can bring, so if somebody's interested, I'm sure they could come.

The architectural tour will be in the city and will focus on C. Emlen Urban, the Lancaster architect's work. We're going to be having walking tours throughout the day on a Saturday.

OUL: Do you have a favorite time period or style of architecture?

Keperling: There's parts of each style that I really like. I was born in Colorado and we moved [to Lancaster] when I was 10, so it's probably that Midwest/Mountain West influence and then my dad's family is in Oregon.

I like bungalows and that midcentury modern; I have a soft spot in my heart for those even though that's not the type of work that we usually do.

One of the things we've been talking about here with our surveys is that when they did those surveys, there was a definite bias against the early 20th century architecture. They weren't seen as being as valuable as the Colonial or Victorian, so I would really like to redo our surveys and include some of those buildings.

It's really hard when someone comes to us for a demolition permit and [the building in question] wasn't included in the survey or it was rated lower even though it could be an architecturally important building.

OUL: Can you expand into what this survey is?

Keperling: So there were three different surveys that were done in the '90s, '80s and '70s where they actually had volunteers go out and survey the entire county and a majority of the historic properties.

It's a great resource for anybody whose interested in learning more about their property or what it looked like, at least during those snapshots of time, and there was some historical research that people did when they were out doing the service.

One of my complaints about the surveys, though, is that they're inconsistent. I'm guessing that they let the volunteers do what they wanted because someone that was in charge of Columbia went around and photographed every single building. We have four binders of Columbia! But then in Lancaster Township, it's just Schooling Hills.

OUL: It becomes very subjective then and perhaps some buildings are getting missed because to some they're "too new." Is that what you mean?

Keperling: Yes, actually an example of that is that back in February, they started developing a proposal to build a condominium where the Hager parking lot is now.

There's two historic buildings there: There's the Potts building, which was a C. Emlen Urban building also, and they proposed to save the façade. Then there's a one-story porcelain enamel tiled gas station.

One day I was laying on the sofa and it was really bothering me because I felt like that cute little enamel building needed to be preserved. So I sent an email out to the board like, "Is it okay if I put out a press release and then I put it on our Facebook?"

I was nervous that people would say that it wasn't historic or not that important, but the response was overwhelmingly positive and people were excited. Somebody reached out from that and offered to move the building and turn it into an art gallery, so it'll get saved.

OUL: Does that subjectivity come into play with other aspects of what you do and what the Trust does?

Keperling: I do think it's subjective because it's what's important to you at the moment. Typically, I go back to the National Park Service guidelines of what makes historic property. So it's something that's more than 50 years old, site of a significant event or significant architecture. There's also a category for archeology, but that's not something that I usually worry about.

For the 50 years, you're getting into the 1970s because it moves up every year, but I think that people don't usually think that the things that are being built while they're alive are as important as the things that came before them.

One example of a building that became historical because if its significant event was the midcentury modern hotel that Martin Luther King was assassinated at, the Lorraine, immediately got put on the National Register even though the building wasn't old enough.

The buildings that were built after World War Two are harder to preserve just because those materials aren't built to be repaired. They're built to be disposable and replaced, so it makes it hard to preserve those, but they are an important part of our history.

OUL: As we wrap up our conversation, what should people in Lancaster know about historical preservation that they don't already?

Keperling: I would want them to know that the Preservation Trust is here to help and because we can't be in every part of the county, it's really helpful when people let us know what's happening in their neighborhoods. If we can help, we will do what we can to help preserve any property because we are county-wide, not just in the city.

Preservation is important for not just preserving the way our communities look and stopping progress — because a lot of people think preservation is trying to stop progress — but also as an economic development tool.

When you preserve a building, the majority of the money does stay local, because it's mostly labor, rather than materials going to a large corporation. And it's been shown to actually help communities with job creation and economic development.

If people could realize that you can preserve buildings and have growth and progress, I think that would help the perception of historic preservation.