(Editor's Note: This story and its companion piece were researched and written by high school student Gifti Galdi as part of the second session of the Refugee Youth Journalism Project.)

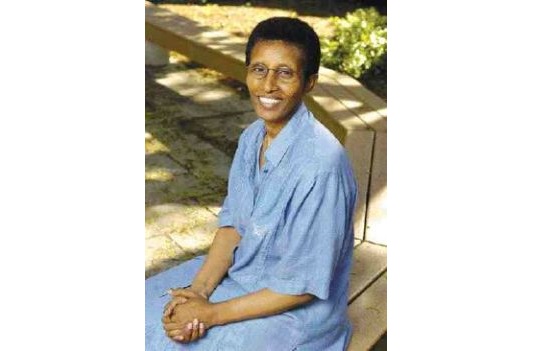

“Where are the women?” Professor Kuwee Kumsa, Associate Professor of Sociology at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, asks when discussing the role of Oromo women in the house, church, and wider political systems.

Related: Immigrant Oromo women challenge patriarchal norms

Kumsa is an immigrant from the Oromia region of Ethiopia, who studies Oromo culture and identity. Her work promoting Oromo Women’s Rights in Ethiopia led to a nearly decade-long detainment by the Ethiopian government, after which she fled and was resettled in Canada.

According to Advocacy4Oromia, “Housekeeping and child upbringing are a women’s domain, however, political and military issues are reserved for men.”

This doesn’t capture the reality. Women make contributions to all levels of society but are not given the credit they deserve and are limited as to when they can raise their voices.

“In traditional culture, the role of Oromo women is very crucial to the maintenance of a successful household,” Kumsa said.

She adds: “However, that role and many others they play are often overlooked and downplayed.

“Oromo women have been the backbone of their culture, politically, domestically, and spiritually, but they have not always been welcome to take part in both societal and political discussions, therefore excluding them from making crucial decisions.”

'I just want to make sure you get home OK'

In traditional Oromo culture, surveillance of women and girls is harsh. Kumsa describes her experience in which her mother would stand outside by their house door and make sure her daughters came home at the same time every day.

If they did not come home on time, they would be beaten. Surveillance begins from an early age and continues until girls are married off.

The reason for this level of surveillance isn’t just about safety; it’s about purity. Oromo women usually start marrying around the age of 15 and are expected to be virgins at the time of their wedding ceremony. Men, on the other hand, often do not marry until around age 28. They expect their brides to be “pure.”

“Virginity is greatly valued in the community,” Kuwee remarks.

This mentality derives from the belief that if a girl was not over-monitored she is up to no good. If she is not a virgin, shame is brought upon the family and she is unlikely to ever be married. If she is a virgin, the marriage process goes forward.

But once married, says Professor Kumsa, “it’s like the girl is going into exile.”

Though traditions are changing in Oromia, “rural areas still uphold the tradition of “blind marriages, a type of arranged wedding set by parents,” she states.

According to anthropologist Seyoum Worku, women must marry outside their immediate circle, their so-called “sub-clan.” For that reason, the woman is a stranger to her new social group and has to adjust her way of life to her new circumstances.

A 'mini-revolution'

Iftu Gemeda is an Oromo woman who lives in Lancaster. In her view, “becoming open-minded has led us to a mini-revolution.”

Gemeda believes women always have played a crucial role but were not always given the recognition deserved.

Thus, “the shift of gender roles in Oromo culture in the United States, is not a rejection of our diverse culture, but an implementation of Oromo women’s voices being heard.”

Preserving culture while being open-minded and embracing other thinking styles, interests, and different traditions is the best way of growing, she said:

“Due to the progressiveness of our community, we can host our own meetings, make our own decisions, and ensure our voices are heard."