(Editor’s note: This essay is part of a collection examining the intersection of history, memory and education in connection with Juneteenth.)

As president of the Lancaster Branch of the NAACP and as second vice-president of the Pennsylvania State Conference of the NAACP, I ask and challenge all of us to embrace the NAACP’s vision and mission, as stated in the NAACP Constitution.

We envision a society in which all have equal rights and there is no racial hatred or racial discrimination. Our mission is to ensure the political, educational, social and economic equality of rights of all persons.

These are inspiring words. For generations, people, fighting for justice, have been moved to action by them. They also are overwhelming words. When we each walk daily through our world today, we encounter issues and structures that in obvious ways and in subtle ways run counter to this vision and mission.

I would like to challenge us all to see and reduce the inequity around us. In the words of Mahatma Gandhi, the great leader of India and proponent of nonviolence, let us be “the change we wish to see in the world.”

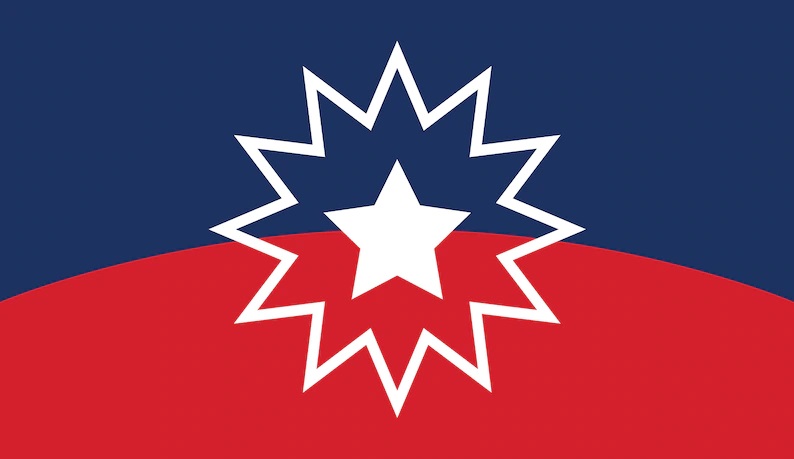

On Juneteenth National Freedom Day, we celebrate the end of race-based chattel slavery in the United States. We celebrate this important event in our political, economic and social history. At the same time, we acknowledge the burden that slavery has left for us all.

As a Black man, descended from people who were enslaved in the state of South Carolina, this burden is mine. As a descendent of people who went to court in South Carolina to plead for equal education for their children, and whose case became part of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. Board of Education, this burden is mine.

It is also the burden of every person in the United States where the legacies of slavery and racial prejudice have stalled progress and economic development. Unjust and inequitable laws and policies have hurt us all in the past and continue to throw spokes in the wheels of progress to this day.

Juneteenth National Freedom Day commemorates a major civil rights episode in the history of the United States, the emancipation of all people who were enslaved.

The day itself is the anniversary of the public announcement of the end of slavery in the state of Texas, on June 19, 1865. Six months later, on Dec. 6, 1865, chattel slavery was ended throughout the United States by the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Juneteenth began as a regional celebration in Galveston, Texas. Its meaning has slowly but surely been embraced nationwide.

In 2001, Pennsylvania’s House Resolution 236 officially designated the third Saturday of June as Juneteenth, marking the state’s first official recognition of the holiday. In 2019, Gov. Tom Wolf signed into law Act 9, designating June 19 as “Juneteenth National Freedom Day” in Pennsylvania. Wolf made it a holiday for state employees the following year.

The 13th Amendment states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Unfortunately, the Punishment Clause of the 13th Amendment eventually was used to justify such cruel practices as convict leasing. Convict leasing and other cruelties of the criminal justice system extended some of the degradations of slavery long after it was abolished. Nevertheless, the 13thAmendment’s significance stands firm. The amendment was a major step toward completing the promise of the U.S. Constitution, as stated in the Preamble: “To secure the blessings of liberty.”

We must remember the impact of race-based chattel slavery on our history. Slavery and the resulting racial discrimination continued to have a profound impact on our laws and policies. These impacts are felt to the present day. Many of the equity issues that we face today in our communities and nation can be traced to the institution of slavery. Slavery led to secession, Civil War, emancipation, and reunion. But the impact of racial distinctions and disparities in many aspects of our civic life continues.

One example is the difference in family wealth between White families and Black families, commonly called the racial wealth gap. Economic historians William Darity and A. Kirsten Mullen published an award-winning book in 2020, “From Here to Equality.” It was so well received that a second revised edition was published in 2022. The book analyzes the ways in which discrimination have cut off economic progress for Black Americans.

The authors say family wealth is the “best single indicator of the cumulative impact of White racism over time.” They state that, in 2016, the median household worth in Black families is one-tenth that of White families: Just over $17,000, versus just over $170,000. That is, for every $1 of net worth that a White family holds, a Black family holds 10 cents. The figures were taken from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances published by the Federal Reserve — in other words, a reliable source.

As people dedicated to good health care for all, let us think about the impact of the racial wealth gap on the U.S. health care system. What does it mean for a family’s ability to seek medical care either in an emergency or for a chronic condition? What does it mean for a delay in seeking care that might make a condition harder to treat? What does it mean for the ability to afford medications and to use them as directed? What does it mean for the ability to afford the health insurance that guarantees good care?

For Black families, the racial wealth gap does not result from behaviors or opportunities of individual family members. It does not result from lack of knowledge about saving and investing. It does not result from lack of education or credentials. It often results from Black exclusion from laws and policies that helped build generational wealth in American families.

We need to look back into history for these laws and policies, but we can still see their effects today. Between the 1860s and the 1930s, the Homestead Acts transferred public assets, including 246 million acres of land, the equivalent of six large states, to families. The Homestead Acts largely excluded Black people. Since 1994, the G.I. Bill has offered educational and training opportunities and access to low-interest mortgages. It was a roadmap to home ownership and better household net worth for many veterans, but it accommodated Jim Crow laws, excluding many Black Americans from its benefits.

It is not just the legacy of race-based slavery that we bear, but the legacy of the Jim Crow era and of the discrimination encoded in United States laws and policies.

We must face this history, and our city, region and nation must be transformed by our understanding. A national day of remembrance is a fitting part of this work.

Celebrate Juneteenth. Support the work toward the equality and justice and the peace that must follow in its wake. We did not construct this long history of systemic discrimination, but we must help to dismantle it. Let’s not be overwhelmed by the complex legacy of discrimination that was built up over decades. We, each in our own sphere, can strive to see and dismantle inequities.

We have good examples in our own region and our own history.

Thaddeus Stevens, a White member of the US House of Representatives from Lancaster, and Lydia Hamilton Smith, a mixed-race single mother who served as his housekeeper, business manager, and confidante, risked their very lives and their livelihoodsfor justice during and after the Civil War.

We see Thaddeus Stevens’ commitment to building social, economic, and political power for all people. He worked tirelessly public education in Pennsylvania and for the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment which confirmed citizenship for all people born in this county, including those who had been enslaved.

We see Lydia Hamilton Smith’s commitment to gaining economic opportunity. She purchased property, including the home and office building of Thaddeus Stevens, which had been her home for many years. She developed a successful business in Washington, D. C.

Let us also remember the work of Medgar Evers, the NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi, who was murdered on his own doorstep in Jackson, Mississippi, 61 years ago on June 12, 1963.

In this moment in our country, we must embrace the example of these forbearers. We must work tirelessly for equity, not only in politics and voting rights, economic opportunity, and education, as they did, but also in health care and environmental issues. These are strategic initiatives of the NAACP.

In our time, we see political divisions that cause some people to hark back to the time of the Civil War. We see deep anger and ill-will. We all seek a harmonious and peaceful community. We must remember that if we want peace, we must work for justice.

The struggle for freedom and equality in this county is a long, strenuous journey. We must take up our part in this important work.