So, what went on in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865, anyway? Why is it important to Pennsylvania in general, and Lancaster in particular? Why should we care today?

Let me begin by addressing the myth that the enslaved population of Texas was somehow in awe of the diplomacy of U.S. Gen. Gordon Granger. Or that his words were transformative. It was not a matter of the enslaved “not knowing” they were already free at the cessation of the Civil War. Texas was still under heavy Confederate siege and the enslaved could not resist, let alone exercise their freedom, on June 19, 1865.

Besides, Gen. Granger wasn’t talking to them; he was talking to their masters, many of whom were Confederate soldiers that had not laid down their arms. Some had joined vigilante gangs forming nightly raids on Union sympathizers. The Emancipation Proclamation was addressed to them!

The proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 while the war raged mainly in the South. Lincoln assigned very few Union resources for the War in the West.

Although the Confederate army surrendered to the Union army in Appomattox in April 1865, the fighting in Texas, the westernmost Confederate state, raged on.

Gen. Gordon Granger landed on Galveston Island on the evening of June 18, 1865, accompanied by 2,000 Union soldiers.

Fate or providence arranged that several units of newly formed Black regiments were also in the Galveston harbor June 18-20, 1865, overlapping with Granger’s famous issuing of General Order No. 3.

At war’s end, many Black soldiers had re-enlisted in the victorious Union Army. Infantry soldiers were reorganized into the 9th and 10th Cavalry, nicknamed the Buffalo Soldiers. They were headed for the Indian Wars in the West.

The reconstituted regiments had set sail from Virginia to South Padre Island, Texas. But storms and rough seas on the voyage sapped the infantry of coal and water. Their ships were diverted to Galveston for supplies.

By all accounts, they intended to rendezvous under the command of Gen. George Custer.

Custer had distinguished himself as a daring yet reckless officer at Harper’s Ferry during John Brown’s raid. He was heralded as the dashing young commander who led Union troops successfully at Gettysburg. After he pursued Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee to Appomattox, Custer moved quickly up the ranks.

The newly minted Buffalo Soldiers made up as much as 20% of the calvary. Their ranks included 18 Medal of Honor recipients.

Custer was offered the position of command over the Buffalo Soldiers but adamantly and openly refused to lead Black men who had hardly stepped away from bondage.

The Christian Recorder, an African Methodist Episcopal newspaper, reported that Custer had said: “Black men will not fight. They are superstitious and afraid of the Natives. They will only turn and run.”

The Buffalo Soldiers concluded, “Thank God that we were not assigned to Custer!”

Gen. Granger engaged the Buffalo Soldiers and they marched into town with his force of 2,000 on June 19.

He had planned to stage a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation followed by an announcement of Executive Order No. 3.

The people heard him coming long before his entourage arrived. It was “high June” and the fields and factories were bulging with production.

Confederates throughout Texas were in no mood to hear the Emancipation Proclamation. It was Lincoln’s document of ultimatum, and they were not having it.

Texas had seceded from the union on March 1, 1861, just days before Lincoln’s first inauguration. The state did not return to the union until 1872.

When Granger arrived, the majority of the 250,000 enslaved people in Texas lived on the mainland. Thus, Galveston Island was relatively easy to overwhelm. It would be a different story in the interior, where fierce resistance lasted for six more months. It would take all Granger’s men to put the Confederate renegades and vigilantes down.

On the morning of June 21, Gen. Granger ordered the Buffalo Soldiers to stay behind to protect the property of the loyal White Texans and the rights of the newly emancipated Black men and women.

Black folks in Galveston were amazed that Black men in blue uniforms had arrived to protect them. White folks in Galveston were appalled at the very thought of obeying a Black soldier’s orders.

No, it wasn’t a day of jubilation in Galveston nor in Central Pennsylvania.

One of my father’s favorite sayings was “Don’t forget to read the fine print.”

So, let’s go back to May of 1861. The war was less than a month in progress and both the Union and the Confederates were at Hampton Roads, Virginia.

Hampton Roads led to the Union stronghold of Fort Monroe under the command of Gen. Benjamin Franklin Butler.

While the town’s residents were in an uproar over the Union advance, most Africans in America were overjoyed by the arrival of the Bluecoats.

The encounters of the enslaved and Union soldiers that day prompted three men of African descent, Sheppard Mallory, Fran Baker, and James Townsend to consider self-emancipation.

The three decided to take advantage of the confusion prevailing among White inhabitants and escape late at night. They slipped into a rowboat and crossed the James River and into Union lines.

Arriving at Fort Monroe, they were brought before Gen. Butler. They succeeded in convincing him that they were being used to build nearby Confederate fortifications on Sewell’s Point. The three encouraged Butler to therefore consider them as weapons of contraband.

All three were considered the property of Hampton resident Colonel Charles King Mallory, a Confederate commander of the 115th Virginia Militia Regiment.

When the Confederate officer showed up the next day to claim his property, Butler refused Mallory’s request.

He informed Mallory that since Virginia now considered itself an independent nation, Mallory’s “constitutional claims’’ to property were null and void. Butler further noted that because Virginia was at war with the United States, he intended to take possession of whatever property he needed.

The news traveled quickly. By May 27, a dozen more enslaved people escaped from Sewell’s Point and turned themselves in as contraband at Fort Monroe.

That June, Gen. Butler informed his superiors that the value of the formerly enslaved persons in Union hands exceeded $60,000.

Hundreds turned into thousands of enslaved people who began to flock to Union troops to turn themselves in as contraband. The issue of contraband brought slavery to the forefront as a wartime issue.

By fall, Butler asked Congress for guidance. He wrote:

“The negroes came pouring in day by day. I found work for them to do, classified them and made a list of them so their identity might be fully assured when I appointed a commissioner of negro affairs.”

The result was the Confiscation Act of 1861, which declared that bondsmen used to aid the Confederate war effort, were contraband — illegal goods — and could be confiscated by Union forces.

Inhabitants of contraband camps soon organized their own leadership and developed systems of self-management. From the beginning, the camps exhibited business ingenuity, creating barter for their services to Union soldiers as barbers, butchers, tailors and tanners, to name a few. Their meager incomes began to develop gradual but measurable Black enterprises in the four years of the camps.

In September of 1862, Lincoln freed all those enslaved in the District of Columbia through executive order. He launched an elaborate reparations campaign, reimbursing enslavers for the value of their emancipated “property.”

Slaveholders in the border states were asked to set an example of solidarity of the Union by basically redeeming their enslaved people for state reimbursement.

President Lincoln went so far as asking his cabinet to explore the cost of compensation to Delaware’s slave owners. The cabinet advised that the cost would be greater than the entire national budget.

Although Washington, D.C., was a territory without slavery after 1862, Black refugees were not completely free from the shackles of bondage. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 remained federal law until 1864; technically, “fugitives” could be returned to their owners in the South even after reaching Washington, D.C., and other free states in the North.

Freedmen from Washington, D.C., headed straight for the Mason-Dixon Line increasing the strain on Abolitionists and Temprance Societies in Central Pennsylvania.

It was clear that the only solution was emancipation through federal force and military might.

The “contraband,” as they became known, were nomadic between 1863 and 1865. They usually lived in camps hastily erected almost anywhere the Union army was stationed.

Therefore, a chain of small towns with names like Little Africa, Freetown, and Jordon proliferated wherever Union forces prevailed. Self-emancipation, self-empowerment, education and economic independence became the reward of their fragile existence in support of Union troops.

That’s why Gen. Granger’s General Order No. 3 and his reading of the Proclamation was so devastating. Contraband camps and shanty towns everywhere were no longer protected by Union forces. Neither could they depend on them for jobs, trade or shelter.

General Order No. 3 advised the emancipated to go back to their plantations and negotiate contracts for wages, housing, and welfare. Right?!

Now, what Black person could have entered a discussion about a fair shake with a person who had laid the whip fiercely to his back simply for looking his former master in the eyes?

Still, the large number of freedom seekers who flocked to Union lines belies the outdated and racist notion that enslaved Africans in America simply welcomed emancipation by singing hymns and strumming banjos. Rather, they seized almost every chance to pursue their freedom, often risking death.

By war’s end, approximately half a million formerly enslaved people had sought protection behind Union lines.

For them, the small print that Gen. Granger read that day in Galveston proved to be devastating. Thousands of Black people across the war zones were turned out from their meagre homes and scattered from their fluid communities that had followed along the lines of battle maneuvers. The no longer were protected.

The fact is that June 19, 1865, created total chaos.

It’s also important to note that some historians dispute that Granger read the orders to the public with any pomp and circumstance during the brief ceremony at Ashton Villa in Galveston.

As commanding officer, Granger’s orders were to simply come ashore and order his soldiers to disperse throughout the town and countryside, advising slaveholders that their enslaved had to be freed immediately. They were then to move on to the mainland to put down renegades and protect the confiscated Texas agriculture and industry.

June of 1865 was challenging time for Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Lancaster too. Despite his poor health, he was shuttled back and forth to Washington by his caretaker and confidante, Lydia Hamilton Smith, to push through the 13th Amendment, the legislation that actually freed enslaved people throughout America.

They were free but still not citizens. The passage of Thaddeus Steven’s landmark legislation, the 14th Amendment, brought citizenship to Freedmen and Freemen.

Throughout time, Black communities have celebrated the self-empowerment that comes with belonging to family and community.

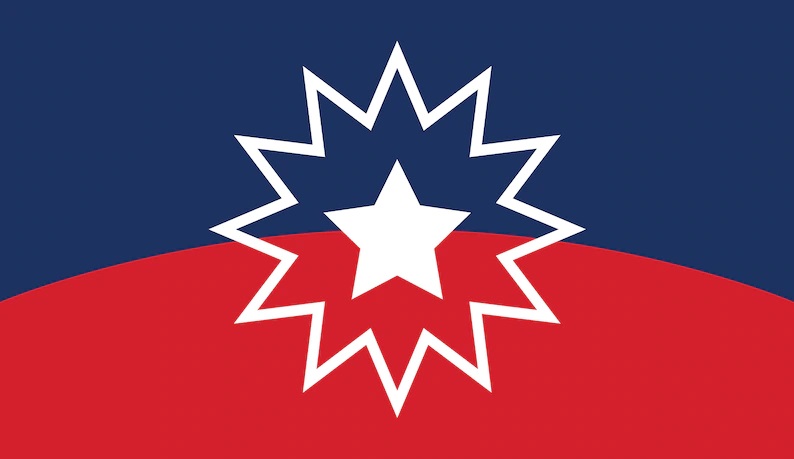

Juneteenth morphed with the times depending on the need for vigilance or jubilation.

In Lancaster, the call to the streets resulting from the death of George Floyd and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement added new gravitas to Juneteenth and changed the paradigm of the day.

It has since become a period of civic dialogue and deep examination of inequalities that still exist in matters of freedom, citizenship, and democracy.

In short, Juneteenth is a day of reaffirmation of one’s commitment to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Folks in Lancaster have planned an abundant cornucopia of commemoration, celebration, and examination. It’s a perfect time to refresh our commitment to fulfilling the nation’s promise of liberty and justice for all.