Her family knew something was wrong with their mother when she forgot how to cook her signature dish of beans and dumplings, Vasthi Dominguez said.

Sure enough, her mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, Dominguez said. She had been a matriarch, the poetic heart of the family and its pillar of strength. The disease took her life in 2019. It was “really tough,” said Dominguez, who served as her mother’s primary caregiver.

Dominguez shared her family’s story Thursday at Lancaster’s first Hispanic Summit on Alzheimer’s & Dementia, hosted by the Alzheimer’s Association Greater PA Chapter in partnership with other area organizations. Conducted in English and Spanish, it sought to raise local awareness of a looming public health crisis.

Related: Organizers envision launching a Lancaster ‘Alzheimer’s Action Network

As Americans age, Alzheimer’s is expected to become an increasing burden, but for Latinos, the issue is especially urgent. Latinos are 1.5 times more likely to develop dementia than non-Latino Whites, and over the next 40-some years, they are projected to have the steepest rise in dementia of any demographic group. By 2060, the Alzheimer’s Association estimates that 3.2 million U.S. Latinos will have the disease.

Latinos with dementia are less likely to be promptly diagnosed and less likely to receive optimal care, said Heather Snyder, vice president of medical & scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association. Many factors are at play, she said, including language barriers, limited access to health insurance and health care, and a lack of awareness around dementia that results in families dismissing its early signs as “normal aging.”

Historically, nonwhite groups have been underrepresented in clinical studies, Snyder said. The Alzheimer’s Association is committed to changing that, she said, and to bringing lived experience from all communities into the conversation around dementia.

It’s “past time” to bring a diverse, inclusive approach to all aspects of the fight against Alzheimer’s she said. Doing so will not only give researchers a better understanding of the biological underpinnings of Alzheimer’s, she said, but also provide insight into the social determinants of brain health, how those social determinants play out in different populations and how best to promote lifestyle modifications that can reduce risk, such as healthy eating, regular exercise and robust, sustained social engagement.

It’s believed that up to 40% of Alzheimer’s cases could be prevented or delayed by targeting risk factors that patients have control over, Snyder said. The payback could be vast: If the average onset of Alzheimer’s could be pushed back by five years, 5.7 million fewer people would develop the disease in coming decades.

It would also give more time for new medications to come online. More than 170 Alzheimer’s-related clinical trials are currently under way; as they wrap up over the next 18 months or so, an “incredible pipeline” of new therapies is expected to emerge, Snyder said.

Robert Torres, secretary of Pennsylvania’s Department of Aging, said dementia is a personal issue for him: He lost an aunt to Alzheimer’s and his mother-in-law was recently diagnosed with early-stage memory loss.

His department oversees an Alzheimer’s and dementia task force that works to improve awareness and care and implement best practices statewide.

Latinos have a proud tradition of providing care within the extended family, Torres said, but it’s OK to seek help outside that network. The sooner families obtain a diagnosis, the better, he said. Dementia patients are often the target of scams, so acting early protects their assets. Moreover, a sufficiently early diagnosis gives patients themselves a chance to weigh in on their priorities and desired course of care while they’re still of sound mind.

Local resources

Between Snyder’s and Torres’ presentations, a panel of service providers outlined the resources available to Alzheimer’s patients in Lancaster.

Connie Metzler, program coordinator for the Memory Care Program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health; and Dr. Robert Shelly of Union Community Care both stressed the importance of early diagnosis and detection; and of taking full advantage of available resources.

“You’re not alone in your journey,” Shelly said.

Adult day care programs and in-home programs can ease the burden for family caregivers and enable seniors to stay in their homes longer than they otherwise could, said Zoe Bracci, executive director at Moravian Center Adult Day Service; and Jennifer Costigan, a supervisor at the Lancaster County Assistance Office.

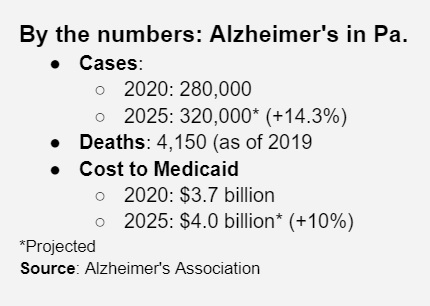

Lastly, there’s the question of paying for services: According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the estimated average lifetime cost of care of a dementia patient is more than $370,000.

Medicaid can pay for long-term care, said Robin Work, an ombudsman with the Lancaster County Office of Aging. But be prepared: Applicants must submit extensive financial records; and after beneficiaries pass away, Medicaid seeks to recover its outlays from the estate.