Advocates for social justice and criminal justice reform filled the Lancaster County commissioners' conference room to call for bail reform at Thursday morning's Prison Board meeting.

They reiterated their appeals that the county focus on treatment and rehabilitation in the design and philosophy of the prison it is planning to build and to aim at keeping its population as low as possible.

Related: Prison reform advocates hold vigil

Related: 'Have a Heart' releases full white paper on prison recommendations

"Our commitment is to come together and to partner with you ... to find a way that we can do better together," the Rev. Jason Perkowski told the board.

Perkowski is a member of the interfaith group POWER. POWER was joined Thursday by representatives of the Lancaster Bail Fund, Have a Heart for Persons in the Criminal Justice System, Put People First PA, Central Pennsylvania Equity Project and local Quaker and Mennonite congregations.

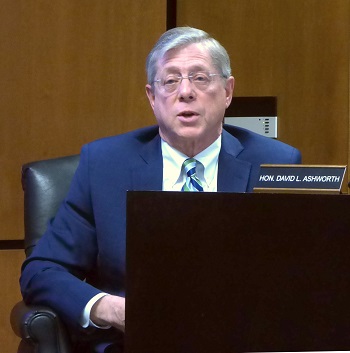

Responding to the many comments, county President Judge David Ashworth said: "To a very large extent, you're preaching to the choir. ... We need all those things that you have been talking about."

Calling for change

Speaking on behalf of POWER Interfaith and other groups, the Rev. Jason Perkowski made the following suggestions to the Lancaster County Prison Board at Thursday's meeting:

- Provide a public defender for bail hearings; or, if not feasible, at least a volunteer advocate who is familiar with the system, along the lines of the Court Appointed Special Advocate program

- Require judges to provide written rationales for the bail amounts they set

- Review prison intake and health care protocols to ensure staff have prompt, full access to incoming detainees' medical records and medications

- Re-establish a commitment review panel; and rigorously examine data and policies on detention, particularly pre-trial detention, to determine opportunities for improvement

- Consider devoting a portion of the new prison site to treatment and rehabilitation facilities

Perkowski said the groups will follow up on the suggestions at subsequent meetings.

Perkowski said the advocacy groups were brought together over concerns about the death last month of John Choma. Choma, 66, who had serious physical and mental health problems, was arrested in late January on a shoplifting charge. On Feb. 2, the Lancaster Bail Fund paid his $5,000 cash bail, securing his release; he returned to the motel where he had been staying, where he was found dead Feb. 7.

Michelle Batt, the Lancaster Bail Fund's founder, has contended that Choma's arrest was unnecessary, and that the disruption may have contributed to his death. Her organization advocates abolishing cash bail.

Statistics show the majority of individuals in Lancaster County Prison — 69% as of January — are pretrial detainees and have not been convicted. Have a Heart and the other groups contend the county could do much more to reduce that count.

But bail policy is largely outside local control, Ashworth said: Judges in the county have some discretion, but they work within a framework established by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, following the law as enacted by the state legislature.

That's where reform would have to come from, and where proposals should be directed, he and Commissioner Josh Parsons said.

As for diverting offenders into treatment programs, Ashworth said he's all for it: He started the county's first treatment court 17 years ago.

There are fewer mental health facilities and less access to treatment than there used to be, but that's not the court system's fault, he said. Judges recognize defendants are frequently struggling with mental health and addiction, and "everyone involved wants to address these issues," he said.

Asked how the county could lower the prison's headcount, Parsons said the reduction seen in the past decade — the prison's population is down from around 1,300 in 2012 to an average of 756 last month — came from streamlining court operations, a process he oversaw at the time as clerk of courts. It would be wrong, he said, to set an explicit numerical goal.

Re-entry coordinator Christina Fluegel provided an answer to a question asked last fall by then-Commissioner Craig Lehman: How many pretrial detainees are first-time offenders charged with non-violent crimes?

As of Feb. 5, there were nine, Fluegel said, plus one individual sentenced at commitment. Their bail ranged from $2,500 to $250,000.

That low number confirms what officials had expected, Parsons said. District Attorney Heather Adams, after quickly reviewing the details of the criminal charges and bail amounts, said she saw nothing out of line.

Fluegel noted the information had to be gathered docket by docket: It took her about 70 hours to compile the report just for that one day.

Tammy Rojas of Put People First PA called on the county to support the creation of a state Public Healthcare Advocate; to build a prison with less capacity than the current one; and to redevelop the existing prison property on East King Street in ways that meet the housing and health care needs of Lancaster's poor.

She and Matthew Rosing, also of Put People First, took issue with comments Ashworth made at February's Prison Board meeting. Responding to Batt, Ashworth had said Choma's bail was appropriate and that posting bail for arrested individuals isn't always optimal: Often, he said, "the best help that they can receive are the services that are provided in prison."

Rojas and Rosing both said they landed in Lancaster County Prison earlier in life, due to decisions resulting from mental health issues and trauma, and both said the experience further traumatized them.

"Jail is not and never will be the best place for a person in trouble," Rosing said.

Ashworth said neither he nor any other judge prefers to incarcerate people if a better solution exists, and his earlier comments should not be misconstrued as implying otherwise: "Nothing could be farther from the truth."

He said a substance abuser recently came before him who could not kick his addiction, despite numerous opportunities for treatment being offered to him. The man's own attorney agreed he would die unless he were imprisoned immediately, Ashworth said.

"The desire was not to incarcerate him, but to get him in a place where he could get the treatment he needed," the judge said. "... It is never my intention or a judge's intention to simply warehouse people."