"There is a better Lancaster out there," Eric Sauder assured his audience Sunday evening.

Sauder is the founder and director of RegenAll, a nonprofit consulting firm that helps businesses, municipalities and households develop climate action plans.

On Sunday, he and a baker's dozen of speakers presented their vision of Lancaster County as a leading-edge exemplar of climate innovation in a TEDx Countdown event at Tellus360.

Over the next two decades, they said, Lancaster County could show the way: reducing emissions, planting trees, rethinking its land use practices, consumption habits and transportation choices. Sauder called for Lancaster to achieve carbon neutrality by 2040.

Lancaster County has unique advantages, Sauder said: It has a strong "brand," it is small enough for coordinated action, particularly the kind of urban-rural collaboaration that he thinks is essential, but it is large enough for those actions to matter; and it has a history of creative risk-taking.

"It's not like this would be the first wild thing that Lancaster has ever done," Sauder said.

Sunday's forum featured speakers in five categories: Natural systems; food and agriculture; the built environment; the economy; and community.

Here are capsule summaries of each presentation:

Natural systems

• WATER: Allyson Gibson, Director of strategic partnerships and programs, Lancaster Clean Water Partners; and Jenna Mitchell Beckett, Pa. state director, Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

Restoring streams and combating climate change go hand in hand, Gibson and Beckett said.

Lancaster County is only 15% forested, and it has the largest number of dairy cows of any county in the Chesapeake Bay. Planting trees, especially along streams as riparian buffers, protects water quality even as it increases carbon dioxide absorption.

The private sector is increasingly working with nonprofits to promote and fund best practices, they said. They urged the audience to support those efforts and advocate to companies, municipalities and their neighbors to continue building momentum. "Be a leader," Beckett said.

• LAND: Phil Wenger, president, Lancaster Conservancy

It's easy to feel hopeless when precious habitat is eaten up by development, government declines to act and actions by individuals appear insufficient to turn the tide. Wenger proposed what he called a "third way": Protect remaining natural areas and restore areas already compromised.

The conservancy does the former, he said, and anyone with a lawn can do the latter: Replace your mown grass monoculture with native trees, plants and wild grasses. Lancaster has an estimated 100,000 thousand acres of mown lawn (about 1/6 of its land area); much of that could be turned into "mini nature preserves," Wenger said, increasing carbon capture and enhancing biodiversity.

Food & Agriculture

• FOOD: Hawa Lassanah, founder, Discerning Eye Community Agriculture (DECA)

Lassanah encouraged the audience to imagine what an ideal, food-secure Lancaster County would look like in 2040.

DECA is her answer. It consists of three subsidiaries: Backyard Farming Cooperative, which encourages backyard gardening; DECA City Farms, an urban farming startup employing sustainable practices; and DECA City Provisions, a "value-added" food brand.

The companies "rethink the entire local food system," eliminating waste, building wealth and returning agency to marginal and vulnerable communities, Lassanah said.

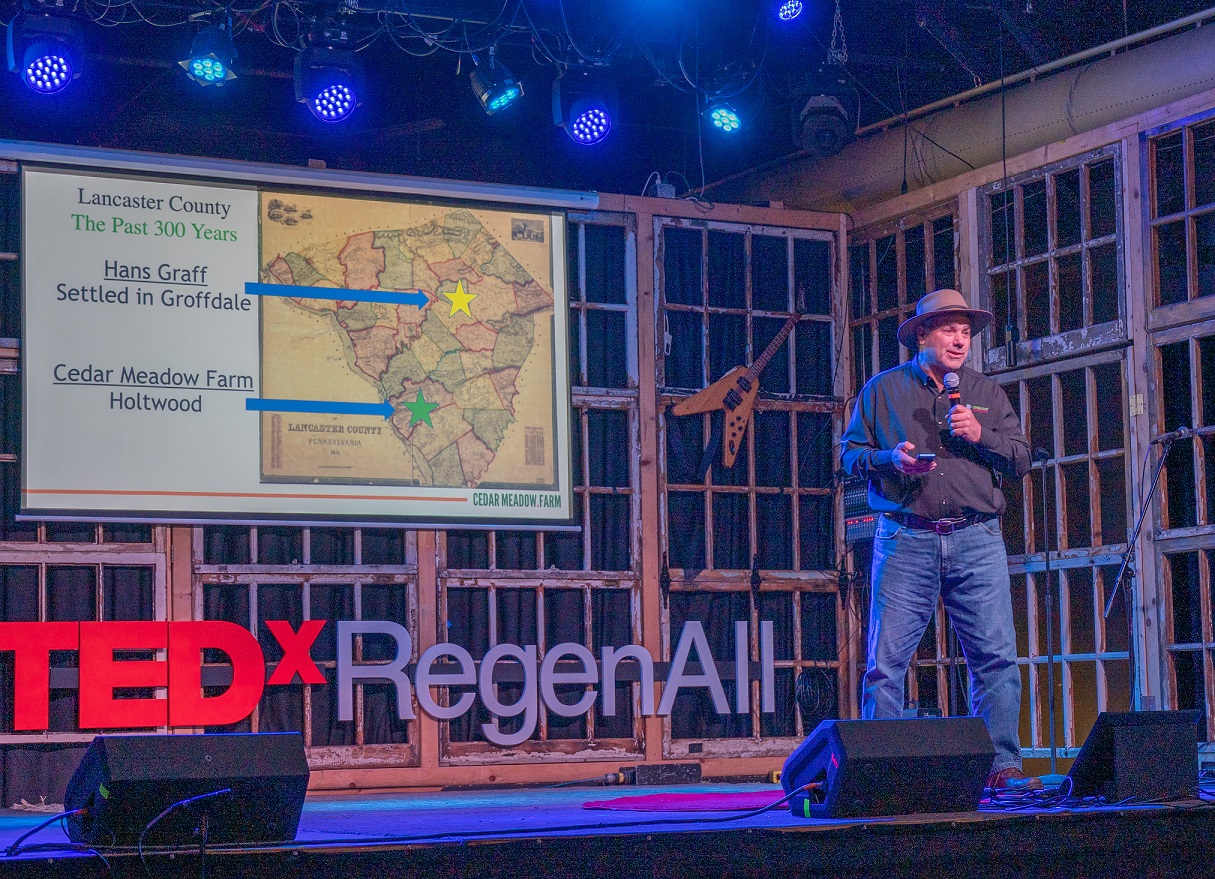

• AGRICULTURE: Steve Groff, cover crop coach, Cedar Meadow Farm

Groff, owner of Cedar Meadow Farm, has been a leader in the cover crop and no-till agriculture movements. He imported the first cover crop roller to be used in the U.S. and developed Tillage Radish, a cover crop that creates healthier soil. He is now planting CBD hemp as a cover crop and working with Penn State Hershey to research CBD oil's cancer-fighting properties.

Lancaster has led the way on agriculture throughout its history and can continue to do so to build a more resilient world, Groff said.

"Would you join with me in this commitment to change the world, starting here in Lancaster County?" he asked.

Built Environment

• ENERGY: Marcus Scheffer, president, Energy Opportunities

Scheffer was a pioneer in the LEED (Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design) movement and worked on thousands of LEED projects during his career. But he said he has come to realize that incremental change will not yield the scale of results needed to combat climate change.

"I think humanity's world view has to change," he said. Paraphrasing ecologist Gregory Bateson, he said, "The way humans think and the way nature works are not in alignment."

• ARCHITECTURE: Max Zahniser, CEO, Praxis—Building Solutions

In his talk, Zahniser offered an assortment of "principles for regenerative architecture." Among them: Work in the places that need healing most; practice true collaboration; embrace innovation; reject "realism" and do what has to be done.

By way of illustration, he mentioned Project THRIVE, a project to build a house for Ron Rambo, a Lancaster native with cerebral palsy. "THRIVE" stands for "Transformative Habitation for Regenerative, Inclusive, and Vital Ecosystems."

• TRANSPORTATION: Michael Jennings, industrial designer

Jennings offered a "blue sky" vision of a transportation system reconfigured around small, lightweight autonomous electric vehicles that would offer on-demand taxi service -- in Jennings' terms, "personalized mass transit."

The worst possible outcome would be swapping internal combustion engines with electric ones and leaving the rest of the 20th century transportation model intact, he said.

Instead, he envisions electrification and artificial intelligence as part of a suite of systemic changes yielding a vastly better world, one without 90% to 95% of current vehicle emissions, 99% of accidents and 80% of parking garages. In Lancaster, he envisions a new "Central Park" occupying the space taken up by the Prince Street garage and the privately owned Hager parking lots, with a two-level underground autonomous vehicle storage and charging hub underneath.

Adapting a Rolling Stones lyric, he said: "You don't always know what you want, but if you try sometimes, you get what you need."

Economy & Community

• CITIES: Jess King, Chief of Staff, City of Lancaster

King outlined Lancaster's climate action plan, which calls for pursuing 25 strategies in six categories: Energy, vehicle fleet, water treatment, trash & recycling, culture and carbon offsets.

The majority of the city's energy consumption stems from water and wastewater treatment. Reducing wastewater inflows would help trim that consumption, and also is critical to the city meeting its obligations to reduce its sewer system overflows under the federal consent decree it signed in 2017.

Even if city government hits its marks, it accounts for just 3% to 4% of total city emissions, King said. That's why it needs buy-in from everyone else: Businesses, residents, other municipalities, county government and so on.

• BUSINESS: Samantha Veide, associate director for the Americas, Forum for the Future

The private sector is at a crossroads, Veide said. Companies must look beyond the goal of maximizing profits and think deeply about the health of the systems that they operate within and depend upon.

She called for Lancaster's business community to be a trailblazer in the "regenerative business movement," and to evaluate their operations according to the five thematic areas outlined by Marjorie Keller of the Democracy Collaborative: Purpose, Financial Flows, Governance, Networks and Ownership.

• REFUGEES: Matt Johnson, refugee community organizer, Church World Service Lancaster

Climate instability is one of the main drivers of political instability, Johnson said. A case in point: The years of droughts and food shortages that most analysts believe set the stage for the Syrian Civil War.

In coming years, the number of people displaced by climate change is expected to grow dramatically. There are two ways to interact with refugees, Johnson said: As people whose circumstances are utterly foreign, or as "fellow travelers," someone whose humanity you acknowledge and whose plight could be yours if things were different.

The latter viewpoint, "seeing ourselves in others," is fortunately prevalent in Lancaster, Johnson said, and it's key to breaking through our mental blocks and beginning to treat climate with the appropriate urgency.

• COMMUNITY HEALTH: Alice Yoder, executive director of community health, Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

Consider a 60-year-old with a chronic health condition, Yoder said. In 2040, when that person is 80, life will be grim indeed if current trends continue. Intense heat would limit time outdoors, reduced crop production would limit healthy eating options; lack of accessible transportation would leave the person feeling isolated.

But "trends are not destiny," Yoder said. If we prioritize active transportation, sustainable agriculture, urban reforestation and green energy, that 80-year-old could enjoy playing with grandchildren in a park, eating locally sourced produce, and walking or biking to meet friends and take part in community activities.

When it comes to overall health, just 20% stems from professional care; a full 80% depends on social determinants. By making the earth healthier, we will make people healthier, Yoder said.

"We are all health care workers," she said, tasked with saving our patient, the planet itself.

• EQUITY: Kevin Ressler, president and CEO, United Way of Lancaster County

Ressler used the global garment industry to illustrate the complex interconnections of history, economics, oppression and exploitation that he said must be untangled, understood and reshaped to achieve sustainability and social justice.

"Our clothes today are still connected to decisions made hundreds of years ago to enslave people," he said.

He urged his audience to make significant changes in all aspects of their lives. People with influence and privilege, he said, have a responsibility to take up the burden of working toward equity.

Imagine, he said, a table where the two hosts gorge themselves on all the food, leaving just scraps at the end of the meal for their guests, yet congratulating themselves on their generosity.

"I hope that in 20 years we're no longer saying that it's OK to give back of our abundance at the end of our life," Ressler said, "but instead we ask the question, 'Why did you take so much to begin with?'"