Dozens of Lancaster County families who lost their housing during the pandemic are staying in local hotels due to the scarcity of affordable rental units for them to move into.

As of last week, 83 households totaling 163 people were in short-term commercial lodgings paid for by the federally funded Emergency Rental Assistance Program, according to the Lancaster County Redevelopment Authority, the organization that administers ERAP here.

They are housed at a dozen or so hotels, mostly on Route 30, said authority Executive Director Justin Eby. Some are single individuals, some are families with children.

ERAP was intended to make up rent shortfalls so that families could remain in their existing housing. But its protections are not all-encompassing: For example, an ERAP-eligible family can lose housing simply because their lease expired, and their landlord declined to renew it. In other cases, individuals and households haven't been able to find a place to live, or were living in hotels already, Eby said.

Local organizations have long turned to hotels for short-term placements of people when other options are lacking. There has also been a population who, due to poor credit or other factors, rent hotel rooms on a monthly basis. Still, the current numbers are strikingly high.

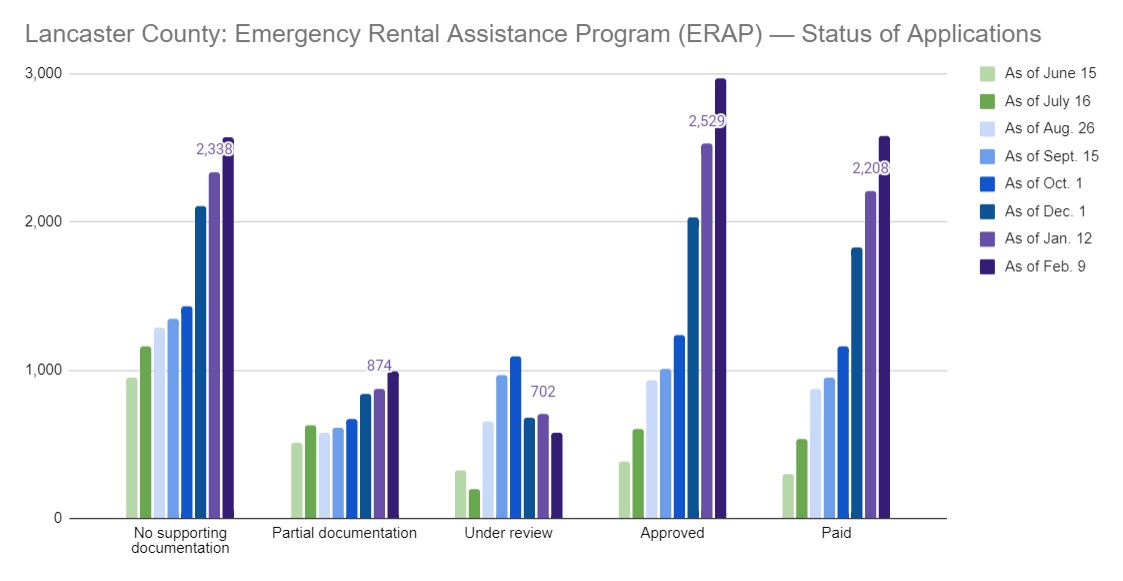

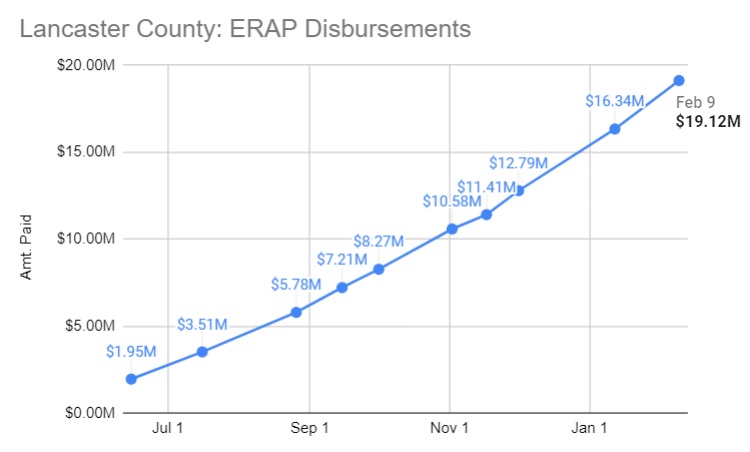

Overall, the number of households seeking ERAP has stayed elevated longer than local officials had expected, said Mike McKenna, CEO of local housing nonprofit Tenfold.

More than 20% of the more than 7,000 applications have come in since Dec. 1. As of Feb. 9, the program has paid out more than $19 million.

The data indicates that many households are still struggling financially, McKenna said.

Finding rental housing in Lancaster County is difficult enough; finding it at an affordable price is even more challenging. Shortly before the pandemic, Lancaster County's vacancy rates were around 2.6% — an exceptionally low figure — and average rent stood at $1,112, according to U.S. Census data.

More than 80% of lower-income households in the county are cost-burdened, according to a 2014-18 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Those households are disproportionately likely to be Black or Hispanic.

A 90-day limit

The redevelopment authority adopted an ERAP hotel policy in December. It provides for stays of no more than 90 days.

For some households, that cutoff is already looming in a couple of weeks. Activists are worried that families could be left in the lurch if they don't find housing by the time their eligibility runs out.

"Where do they end up?" one local advocate, Curtis Jantzi, asked the Lancaster County commissioners at a work session earlier this month. "What's the plan?"

Eby said the authority continues to monitor the situation and is open to revising the policy and offering extensions if needed.

"This is something we knew we had to continue to look at," he said.

Eby said some people erroneously think they can go to a hotel and receive a room paid for by ERAP by self-attesting that they are homeless. That's not how it works, he said. Rather, he said, households must apply for ERAP through the authority first and establish their eligibility. The authority has been sending its policy out to hotels to stem the misperception.

Meanwhile, the authority has to have formal agreements with the hotels it works with. Sites have to be willing to house people long-term and do the paperwork necessary to receive reimbursement. ERAP is a far cry from the standard short-stay, pay-by-credit-card business model that hotels are used to, and not all are willing or able to adjust, Eby said.

It helps that winter is the off-season. Lancaster County has 116 hotels with 8,330 rooms, according to industry research firm STR; in January, occupancy was 38%, STR said.

The ERAP enabling law allows payments of up to 250% of a location's fair market rent, based on Zip code. In Lancaster County the average room rate paid by ERAP is $1,980, Eby said. That works out to $63.87 a day for a 31-day month.

The authority sends out payments weekly, Eby said. In January, it paid $129,993 in ERAP funds to hotels on behalf of 52 households. By way of comparison, that's less than 5% of the nearly $2.8 million the program paid out between Jan. 12 and Feb. 19.

A portion of January's hotel payments consisted of past-due rent for clients' existing stays, Eby said.

Hotels contacted by One United Lancaster did not respond to requests for comment.

The maximum period for ERAP assistance is 18 months, and the program as a whole is scheduled to sunset at the end of September. Eby and McKenna both stressed that their aim is to manage the transition so that households are stable and self-sufficient when aid ends, not at risk of falling back into crisis.

"The goal is to get people into stable housing," Eby said.

For some, case management and wraparound services will be part of the solution, McKenna said; but given the scarcity of affordable housing, zoning reform and other initiatives to boost supply have to be in the mix, too.