A new wave of COVID-19 spread through Lancaster County in August, ending a two-month summer respite.

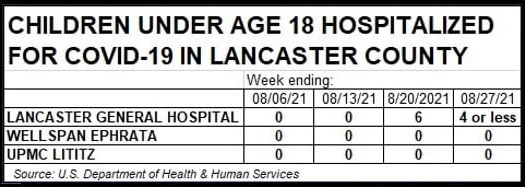

But, as schools reopened, area hospitals reported few serious cases among school-age children and infants. There were just six cases here among those under age 18 in the third week of August and four or fewer in the last week, according to hospital reports to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

None of those children have died, according to the coroner’s office. All can be presumed to have recovered or to be recovering.

There were considerably more cases of a less serious nature among children during the latter two weeks of August, according to the state Health Department.

An average of 23 school-age children (ages 5-18) and five infants (ages 0-4) tested positive here daily between Aug. 16 and Aug. 31, when county schools were reopening. Where those children lived and what symptoms they had, if any, are not publicly available.

Among adults, the trend lines of COVID’s impact in the county were mixed during the month.

New cases increased to a level similar to that of this spring or last fall.

Hospital cases and deaths also rose, but at a slower rate, suggesting that mass vaccination has reduced the number of serious cases. In brief:

• CASES: The state Health Department reported a daily average of 114 new infections in the county in August. That’s above the nine to 18 daily cases in June and July. But it’s far below the 300 to 360 daily cases of this past December and January, when the pandemic peaked.

• HOSPITALIZATIONS: An average of 37 county residents were hospitalized daily with the virus in August. Again, that’s above the low of seven in July. But it’s just a quarter of the 152 patients who filled hospitals here daily in December, according to the health department.

• DEATHS: Seventeen county residents succumbed to the virus in August, about one every two days, according to Coroner Dr. Stephen Diamantoni. That was half the number of April and May (34 and 32) and less than one-tenth of the 207 who died in December.

Those numbers indicate that, while the virus is again spreading through the community, its most serious effects – hospitalizations and deaths – are rising at a significantly slower rate. While new cases are up 32%, hospitalizations have risen 24% and deaths 8%.

That reduction in serious illness and deaths can best be explained by continually improving hospital protocols for COVID treatment, increased vaccination and expanding natural immunity. About 60% of county residents are now partially vaccinated; 55% are fully vaccinated. The number of unvaccinated residents who contracted the disease and recovered, gaining natural immunity, is not known.

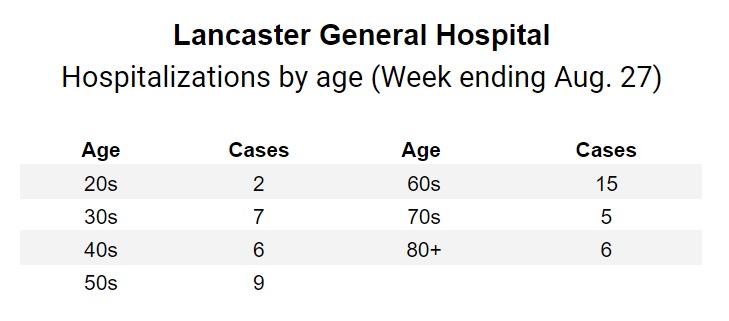

Area hospitals are unwilling to provide up-to-date information on the ages of those hospitalized with COVID. But filings with the U.S. Health & Human Services do provide that information for past weeks.

For the week ending Aug. 27, Lancaster General Hospital reported these hospitalizations by age of residents:

It is notable that the oldest residents here, those over age 70, no longer are the dominant age group seriously ill with COVID-19. Now those in their 50s and 60s make up the largest number of COVID patients.

That change correlates with vaccination rates: About 85% of those age 65+ are fully vaccinated. Among those 50 to 65, the vaccination rates are 15% to 25% lower.

Despite these improvements, some elements of the pandemic here have not changed:

• The virus continues to take the lives of older county residents, not young people. Of the 17 who died in August, 11 were age 80 and over, two were in their 70s, two in their 60s and two in their 50s. All were white.

• No one under age 25 has died here from COVID-19.

• Most new cases continue to be found in Lancaster and its suburbs. The three Lancaster ZIP code areas had a total of 1,033 cases in August, about 30% of the 3,522 cases here.

• The next five highest municipalities were: Elizabethtown (238), Lititz (214), Ephrata (192), Mount Joy (143) and Columbia (123).

Perhaps the most positive news of the past month comes from the county’s nursing homes, once the center of the pandemic. The county’s 32 facilities reported only one death and just 16 cases through the first three weeks of the month, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

That’s a monumental shift from pre-vaccine months, especially the early months of the pandemic, when scores of elderly, infirm residents died in nursing homes. Now mass vaccination and other precautions have all but eliminated virus deaths in homes.

Similarly, the county’s 61 personal care homes reported no deaths, eight resident cases and 13 staff cases.

What these statistics from state and federal sources do not give us are the answers to two sets of pressing questions of public interest.

1) What is the breakthrough rate – the number of COVID cases among the inoculated? Is it so high as to call into question the value of vaccines?

2) How many cases of COVID have occurred among school-age children? How many have been without symptoms? How many are mild, like a cold or flu? How many are serious? In what areas of the county are those cases occurring?

Reports of breakthrough cases give vaccine-cautious individuals a reason to justify avoiding vaccination. If a person can contract COVID even after inoculation, the thinking goes, why get the shots. They may not work.

Similarly, sketchy reports of children testing positive or hospitalized create uncertainty for parents, teachers and schools that want to know the appropriate measures for classroom instruction. The information about serious child cases that hospitals feed to state and federal data banks is dated. It is not correlated with total case numbers in a way that is useful to school districts.

Are most children’s cases asymptomatic? Are serious childhood cases so rare that there is little risk in holding classes unmasked? Or, in recent days, has there been a rising number of serious childhood cases that require hospital care? What ages? What school districts?

The information is tucked away in the reports that hospitals feed to government. But neither government nor medical professionals are willing to provide this information in a way that would guide parents and schools in making rational decisions about maintaining the health and safety of the children in their care.

Likewise, one would think that the state Health Department or hospitals would want to promulgate information about the extent of breakthrough cases. If they are extremely rare – and there is abundant evidence from other states that they are – would not that information assure skeptics that vaccines do the job they are supposed to do?

Unfortunately, Pennsylvania is one of the few states unable to provide such information to the public. (A spokesperson said the department is working on the information and hopes to have it available in the near future.)

Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia do provide information on breakthrough cases, however, and their experience suggests what is occurring here. (Their rates were collected and reported by The New York Times.)

California, which has vaccination rates virtually identical to Pennsylvania, has a breakthrough rate of four-tenths of 1%. Delaware, with a slightly higher vaccine rate, reports the same breakthrough rate.

New Hampshire and Virginia, which have lower partial but higher full vaccination rates, report breakthroughs at five-tenths and three-tenths of 1%, respectively.

Applying the 0.4% rate to Lancaster County, where 8,499 residents have been hospitalized since general public vaccination began in February, one can estimate that about 34 of those individuals contracted COVID even though vaccinated.

According to an Aug. 30 report from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, about 70% of breakthrough cases resulting in hospitalization were among adults age 65 and older.

This summary has been compiled from records of the Lancaster County Coroner’s Office, the state Health Department, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services by researcher Erica Runkles, sociologist Dr. Mary Glazier, data programmer Penn Glazier and journalist Ernest Schreiber.