WILL THE END OF STAY-AT-HOME ORDERS BRING A SURGE OF CRIMINAL CHARGES?

Avid readers of the LNP police log today could see a disturbing pattern:

- A 30-year-old man was charged with harassment after he slapped a person holding a child.

- A 26-year-old man was charged with strangulation after he attacked a juvenile girl and choked her.

- A 24-year-old man was charged with assault and terroristic threats after he threatened a woman with two knives, saying he would kill her and warning that she better sleep with one eye open.

- Another 30-year-old man was charged after he slapped a woman and pulled a broom from her hands, cutting her. He then broke a car window and screamed profanities.

The four cases, all from just one police department, may be a sign that as the state’s stay-at-home orders ease, victims of abuse are finding opportunity to report the violence they have endured behind closed doors.

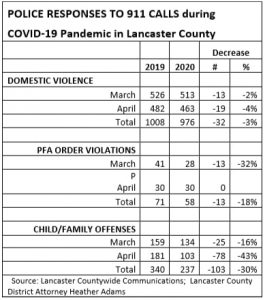

Comparing this March and April to the same months last year, police referred 24 percent fewer cases of child abuse and domestic violence to the office of District Attorney Heather Adams. There were 229 cases in 2019 and 174 this year.

“Because of the stay-at-home order, there is an inability to avoid the abuser,” the district attorney said. “You are in the same household.”

At Lancaster’s Domestic Violence Safe House, director Christine Gilfillan saw a similar trend, “an immediate decline in calls for the first three to four weeks of stay at home.”

Women “were adjusting to the new reality, staying at home, being surveilled in their home,” she said. “They were wondering, how do I reach out when I am in the house all the time with this person. I can’t even make a call.”

A major reason for the drop in child abuse cases, DA Adams said, was the children no longer were outside their homes in settings where they might tell a trusted adult of the violence they were experiencing at home.

“The kids are not at school or church daycare or spring sports,” she said. “They don’t have access” to a teacher or coach. There were other obstacles to reporting, both women said.

“When this first started,” Adams said, “there was a misapprehension that the courthouse was closed.” Some women thought there was no possibility that they could seek help from the office’s domestic violence unit or the courts.

“That’s not the case,” she said. “I have been here every day. The staff is here on a rotating basis to cover hearings.”

At the shelter, a project of the Community Action Program, director Gilfillan learned that some women “didn’t want to come to the shelter because they thought maybe it’s not a safe place” during the pandemic. They worried “What will it be like? Do we sleep in one room?” They feared that close quarters might subject them to the coronavirus.

Both offices addressed those worries and now are spreading the word that they are able to help women and children.

The shelter obtained 10 hotel rooms for women, giving each woman a separate room and bathroom. At the shelter, they cut the number of residents from 32 to 16, again so each woman has her own room and bath.

The district attorney has been working with other county agencies to spread the word that they all are available to help.

“The Children & Youth Agency is working. Law enforcement is working. The Children’s Alliance, the counseling agencies, everybody is still working,” she said.

Women in need of help can call 911 to report abuse, the district attorney said. Some police departments have online reporting services on their website.

Victims also can report abuse by texting the word “safe” to 61222 to reach a hotline advocate.

One of the most effective tools against abusers are protection from abuse orders issued by the courts. Legal counselors are available to help women prepare their request for a PFA, Gilfillan said. The orders remain in force until the courts reopen and hearings can be held to make them permanent. The temporary order prohibits an alleged abuser from contacting the accuser.

In March, 911 calls to report violations – stalking or harassment – dropped by a third. But in April, the system was back on track. There were 30 calls to report violations, exactly the same number as the year before.

(Note: All statistics in this story were compiled by Lancaster Countywide Communications and the District Attorney’s Office.)