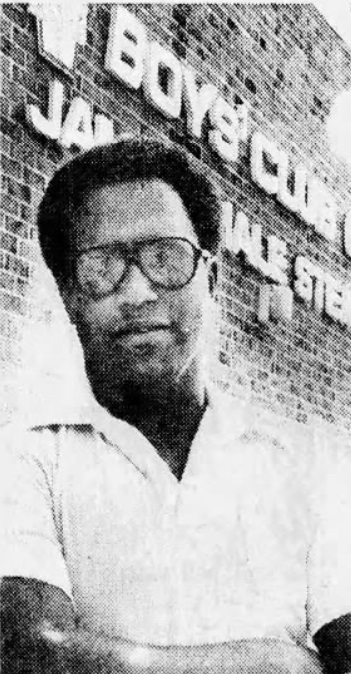

Gerald Wilson, a well-known figure in Lancaster, is a lifelong city resident who has left a significant impact on his community as a police officer, educator and civic leader.

Wilson grew up in the city’s Southeast. He was in junior high when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April 1968, sparking anger and unrest here and nationwide.

“By that time next year, I’m in (McCaskey) high school,” he said, “and those racial tensions carried on through my entire three years.”

During those years, he gained insights into the community’s struggles and the necessity for positive change. After his graduation, he was recruited to be a city police cadet. He became a city officer in 1974, entering law enforcement at a challenging time.

“We had some very rough years,” He said. “They burned buildings down in Lancaster. They had state police in addition to the city police. They had … a curfew placed on the city.”

In the 1980s, the city struggled with a worsening drug problem. Wilson and a group of neighbors helped to open a drug rehab center called Hogar Crea, part of a faith-based international network based in Puerto Rico.

Hogar Crea follows a self-reliance model: Individuals in recovery help lead the organization and mentor their peers. The Lancaster branch was housed at two adjoining row homes that the local group bought on Green Street. A hole was cut through the wall to link them. It accommodated 24 men who lived together.

“They were the counselors. They were the administrators,” Wilson said.

Wilson stayed actively involved with Hogar Crea for more than a decade. It was a great program, he said, but the state was not in favor of it, because it was unconventional and didn’t have professional counselors.

Wilson was promoted to police sergeant and took charge of a drug enforcement unit. He was a lieutenant and shift commander by the time of his retirement in 1997.

He then returned to McCaskey as a criminal justice instructor, a role he held for 14 years, using his experience to educate and guide students.

When asked about the difference between high school in the 1970s versus the 1990s and 2000s, Wilson said, “We didn’t have a say in high school. We didn’t have a personal relationship with teachers or anything like that.

“It changed when I came back. … The kids were very personal with the teachers. It was just a different world.”

In addition to his educational role, Wilson has been involved with many community organizations including the Boys & Girls Club and the Urban League. He helped launch the first Crispus Attucks Community Center benefit pancake breakfast and helped to start the Lancaster Boxing Club there.

Last month, Crispus Attucks’ parent organization, Community Action Partnership of Lancaster County, honored Wilson and his colleague and friend, Leroy Hopkins, with its 2024 Essence of Humanity Award.

A member of the African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania, former of the LancasterHistory board member, he has a deep interest in local Black history. He teaches a genealogy course and has been involved in many documentation and preservation efforts, including the Seventh Ward Oral History Project and an initiative to identify and restore historically Black cemeteries in the area, such as the Stevens Greenland Cemetery on South Duke Street.

He is on the committee to preserve Thaddeus Stevens’ law office as part of its incorporation into the Thaddeus Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith Center for History and Democracy.

“I think it’ll be a centerpiece here in Lancaster,” Wilson said. “A lot of people don’t know about Thaddeus Stevens, but we’re trying to change that.”

Stevens, a prominent abolitionist, played a key role in shaping constitutional amendments during the Reconstruction era. Had Stevens lived longer — he died in 1868 — Wilson believes the Reconstruction Era would have gone “the way it was supposed to be done, not sabotaged the way it was.”

At McCaskey, Wilson would encourage minority young people to consider law enforcement careers. It’s an uphill effort, and the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis had a devastating impact on perceptions among potential recruits.

“Young people are impressionable,” he said. Also, many parents don’t want their children to become police, not only because of the danger but because of the negative view of police among minority communities.

“Look at the small amount of minorities that are on the police department after all these years,” he said. “I left the department 27 years ago, and they still have the same number.”

Wilson underscores the importance of early engagement with young people to tackle these challenges, drawing from his experiences in organizations like the Boys Scouts and vocational programs.

As Wilson continues contributing to civic initiatives, he remains an advocate for inclusivity and understanding in Lancaster.

He said: “The fact that that I was able to represent my community and be in the police department and people knew who I was and still recognize me, I think that’s an example (that shows) ‘You can do that, too.'”