Mark Kelley believes Lydia Hamilton Smith deserves to be much better known than she is.

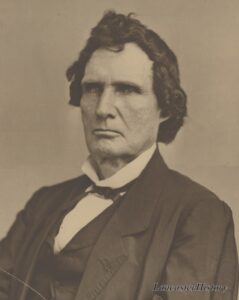

As a woman with Black ancestry in the mid-18th century United States, Smith overcame daunting odds throughout her life, Kelley said. And her close connection with abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens influenced the course of history.

“She knew who she was, and she never apologized for it,” he said. “She fought for her rights in every way that she knew how.”

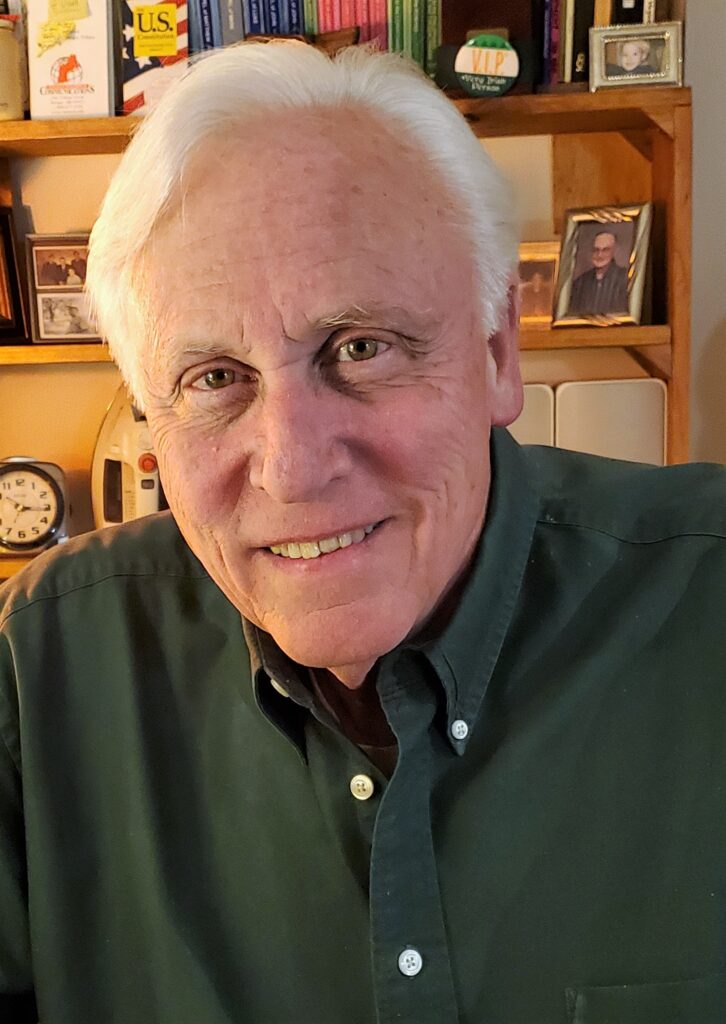

Kelley is the author of a forthcoming biography of Smith, titled “An Uncommon Woman.” Set to be released toward the end of this year by Penn State University Press, it will be the first book-length treatment of one of the most intriguing yet underappreciated women in American history.

Born near Gettysburg around 1814 to a mixed-race mother and a White father, Smith moved to Lancaster in 1847 to become Stevens’ housekeeper. She ran his household, assisted him in business and remained his close confidante for more than 20 years as he rose to become one of the most prominent political leaders of the Civil War and Reconstruction eras.

Smith makes a brief appearance in the Steven Spielberg movie “Lincoln.” The scene depicts her sitting in Stevens’ bed as he shows her the newly passed 13th Amendment abolishing slavery — the first of the three successive “Reconstruction Amendments” that many scholars characterize as America’s “Second Founding.”

Kelley agrees with most historians that the romantic intimacy implied by the scene is possible, but unconfirmed.

“That’s subject to some discussion, whether their relationship reached that level,” Kelley said “What their physical relationship amounted to is really not any of my business in the end. I don’t push to try to prove anything with regard to that. But I do believe that they were very, very close.”

After Stevens’ death, Smith became a prosperous businesswoman. She died in 1884 and is buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery in Lancaster.

“She was an amazingly giving, caring, ambitious, strong, smart woman,” Kelley said, “and she was a woman of color. For all of those reasons she should be celebrated and remembered.”

Kelley, a 25-year veteran of broadcast journalism, holds a Ph.D. from Syracuse University and taught journalism and communications at Goshen College. He is the author of several previous books, including “Rain of Ruin,” a lightly fictionalized account of his mother’s work as a clerk for the Manhattan Project, the top-secret program to build the atomic bomb; and “This Mere Existence: Motivation and Strategies for Restoring Human Rights.”

He is passionate about history and human rights and the intimate connection between them. Distorted history has been used to countenance injustice, and it continues to happen today, he said. Students deserve the truth, he said, expressing hope that it will inspire them to put an end to discrimination in all its forms.

The following has been edited for clarity and length.

One United Lancaster: How did you become interested in Lydia Hamilton Smith?

Mark Kelley: I had never heard of Lydia Hamilton Smith, never even knew she existed, until I watched the Spielberg movie. …

I thought, “I want to know who this is. She lived in Lancaster for crying out loud. I’ve got to find this out.” And when I started to dig into it, it was a pretty amazing story.

A lot of people, when I first started said, “You’re never going find much.” Even though she was, in her time, probably one of the most widely known women in the United States, her memory was just sort of pushed aside.

Biographers of Stephens are still doing that today, which is annoying to me, because it says that they just didn’t look hard enough to find out what she who she was and what she did, and what her role was doing those turbulent years around the Civil War. So I decided I would try to get as much as I could.

OUL: What materials did you draw on?

Kelley: I started by looking at the stuff that was readily available online. There was a lot of repetition. … The thing that people seem to celebrate most is the fact that she became a successful businesswoman. She really was, which is striking, because in the mid-19th century, women weren’t supposed to own anything. She just brushed all that aside and became quite a wealthy woman.

I spent a lot of time in the research library at LancasterHistory. There were any number of documents there that were helpful in trying to put the pieces of her life together. …

Then one of the guys at LancasterHistory suggested that I take a look at Thaddeus Stevens estate file down in the Lancaster County archives. So, I went down there. Nobody had looked at that box for, I don’t know, 50, 60 years, maybe longer. I set out to read every page. It’s all handwritten documents, many of them having to do with court proceedings, related to how they handled his estate after he died.

I ended up finding some amazing information about her. … There’s a record there which details what Lydia did for Thaddeus Stevens in the last five or six years of his life, when he was working for the 13th, 14th, 15th amendments. He was doing critical work, but his health was making it increasingly difficult. He would sometimes be bedridden for a couple of weeks at a time.

Eventually his doctor, Dr. Carpenter, from Lancaster, prescribed medication that needed to be administered around the clock on a very precise schedule, to try to just keep the man alive so he could continue doing his work in Congress. Lydia Hamilton Smith took on that task on herself at some risk to her own health. She would sometimes spend 24 hours a day for weeks on end, sitting by his bedside and caring for him.

In gratitude for the care Smith had provided, Stevens stipulated in his will that she be paid a substantial sum, amounting to several thousand dollars. His executors, however, contested the payment. Smith sued, leading to a court case in which multiple witnesses attested in detail to the extent of Smith’s caregiving.

They ended up with a lot of testimony, people talking about her incredible labors on his behalf over a period of several years, just to keep the man alive so he can do his important work.

OUL: This court testimony has been sitting unnoticed at Lancaster County archives for decades and decades?

Kelley: Absolutely. It was all there. I vowed to read every last word in that in that box in that estate file, and I did. …

The Stevens-Smith Center

LancasterHistory is continuing its planning for a history center in downtown Lancaster commemorating Thaddeus Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith.

The Thaddeus Stevens & Lydia Hamilton Smith Center for History & Democracy will encompass Stevens’ house and law office and the neighboring Kleiss Tavern.

It will be “an interactive history museum and community education facility,” interpreting Stevens’ and Smith’s influence and the foundation of the 20th century’s Civil Rights Movement in the Reconstruction Amendments that Stevens championed.

LancasterHistory hopes to open the center in late 2024 or early 2025.

OUL: I think the term “housekeeper” might be a little confusing. … Wasn’t it more of a household management job?

Kelley: That’s right. She ran the household here and she did the same thing in Washington, D.C. She was a very, very hardworking woman.

They also discussed the (political) issues that he was dealing with. … Some people have tried to say that she didn’t have any involvement in that, that he didn’t talk with her about those things. I absolutely believe she was smart and capable, and I absolutely believe that they did discuss things like that. She was so much more than a housekeeper in that sense.

OUL: How would you describe Lydia Hamilton Smith’s legacy?

She was a person who accepted the challenges that were presented to her. She was born to a single mother who was a mixed-race person. Her father, most likely — we don’t have any written evidence — her father was an Irishman who was running the inn where her mother worked when she was born.

In spite of that rather difficult beginning, she managed to get educated, she developed a tremendous business sense. She married a person of color, a man named Smith, from Harrisburg, but it wasn’t a good situation. He may have abused her a bit. And so when she had the chance, she she took her two sons, William and Isaac, and she came to Lancaster. …

She not only was busy keeping up Stevens’ household, but was starting to invest in real estate and do all those things. Which, again, is a significant accomplishment for a woman of color. In the mid 19th century, it just didn’t happen. They just were not given those kinds of opportunities, but she, she found them anyway.

Stevens had a fairly comprehensive, elaborate Underground Railroad operation going on in Lancaster, and there there’s no doubt in my mind that she helped. … There’s no doubt in the world that she believed that people of color should be free and equal and should have justice in this country.

I think she dedicated herself to that. One of her ways of contributing to that was in her nursing care for Stevens when he was engaged in critical work on behalf of people of color. If she hadn’t done what she did, Stevens’ own physician said he wouldn’t have been alive, when he was involved with the 13th, 14th, 15th amendments.

That seems to me to be a pretty significant contribution to the world. I think she should definitely be recognized for it.