“A lot of these things just add time and money when we need housing now,” Ben Lesher said.

Lesher was speaking to an audience at Hub 450, wrapping up a presentation on The Yards, the project he is developing at the Stockyard Inn site at the corner of Lititz Pike and Marshall Avenue.

The reality of development today, he told his audience, is that it’s relentlessly time-consuming and expensive — and it’s expensive in part because the approval process is so protracted.

That in turn is creating barriers to building new housing at the scale and at the price points that studies say are needed, he said.

Advocates say Lancaster County has a shortage of nearly 20,000 homes that households in the lower half of the income distribution can afford. Lancaster city’s interim housing plan, meanwhile, calls for adding 2,000 residential units by the end of 2026, including 300 affordable units.

There are good intentions behind all the rules and restrictions that developers contend with, Lesher said at the presentation, held late last month. Still, he said, “at some point, I think we need to think as a community, what do we prioritize? What do we want?”

The need for density

Lesher is the founder and president of Parcel B Development Co., formerly SDL Development Co. In 2021, he completed the $18 million, 104-unit Stadium Row project, the first market-rate apartment building of its size to be built in Lancaster since the early 1960s.

This week, he announced plans for a six-story, 130-unit apartment complex in the 200 block of North Prince Street.

Lesher said that in college he seriously considered a career in urban planning. In his development work, he prioritizes density.

“I think density is really important and solves a lot of urban issues,” he said.

The Yards reflects that philosophy. The $59 million project consists of two five-story buildings bordering a landscaped parking lot. They would house 226 apartments — studios, 1-bedrooms and 2-bedrooms — including 45 affordable units. The ground floor allows for 12,000 feet of retail space.

The historic portion of the Stockyard Inn would be relocated to the site’s northeast corner, where it will serve as a clubhouse.

The site is close to the Lancaster Amtrak station, where county planners are calling for transit-oriented redevelopment. It’s adjacent to the Thaddeus Stevens Bridge on Lititz Pike, one of the main thoroughfares in and out of Lancaster. The necessary infrastructure — roads, sewers and so on — is already in place.

“It’s just a really great opportunity to create a vibrant gateway into the city and hopefully catalyze similar investment,” Lesher said.

It helps that the sits just inside the Lancaster city boundary. Manheim Township’s zoning and land development codes have provisions that make dense, mixed-use development much more difficult, including large minimum lot sizes and setbacks, building height limitations and a mandated 1.5 parking spaces per unit.

Review process

The Yards’ process through the city’s review process began with a preliminary meeting in summer 2021. Last week, it secured a key approval, when the city Planning Commission signed off on the project. It has been through the Historical Commission, Traffic Commission and Shade Tree Commission.

Still pending are state environmental permits related to the sewer plan — which required an archaeological evaluation — and erosion and sediment control during construction. Lesher is hoping to finalize those by the end of the year and break ground in early 2024. Construction is projected to take 18 to 24 months.

A potential impediment is an ongoing lawsuit from Robert Redcay’s Brook Farms Development, which owns the neighboring Lancaster Stockyards Office Park.

Redcay alleges the city Zoning Hearing Board improperly granted variances for height and residential density to The Yards; and that the city’s subsequent amendment of its zoning rules was “spot zoning” for The Yards’ benefit.

Making affordability affordable

Including everything, The Yards will cost about $263,000 per residential unit to build, Lesher said.

The 45 affordable units will be interspersed throughout the complex to create a diverse, mixed-income community, he said. Their rents will be based on affordability at 60% of county median income, which currently works out to about $950 to $1,200 a month, depending on apartment size.

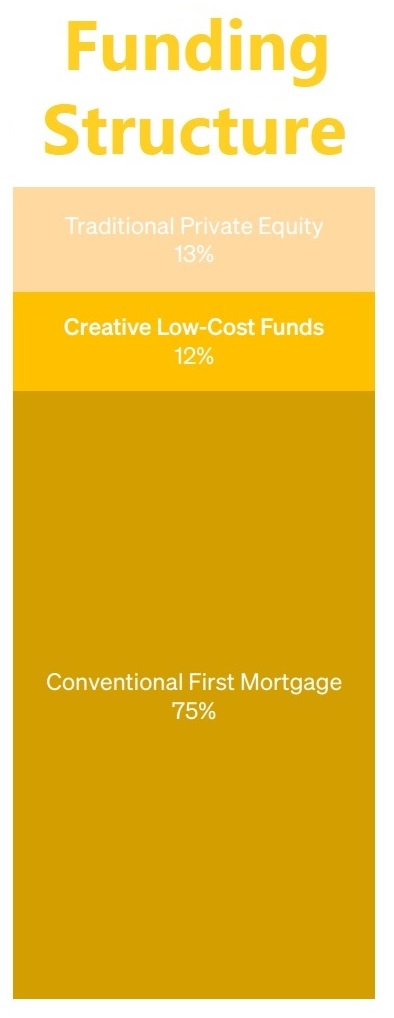

On average, that’s $522 less than market rate, Lesher said. To offset the lower rent revenue, he needs a corresponding amount of low-cost financing; otherwise, the Yards won’t bring in enough to pay its debt service.

The most common mechanism for financing affordable housing is low-income housing tax credits: They’re a key part of HDC MidAtlantic’s mix for The Apartments at College Avenue.

But Lesher said they have significant drawbacks: Developers are competing for a limited supply of the credits, and they add expense and regulatory complexity.

So he’s looking for other options. He estimates he needs about $7 million — either outright grants or loans at no more than 2% interest.

Landis Communities took an analogous approach with Landis Place on King, conducting a public fundraising campaign to support that project’s 10 affordable units.

Lesher has received a $2 million American Rescue Plan Act grant from the city and $1.25 million in ARPA from the county. He’s pursuing a variety of avenues to secure the rest of the funding he needs, he said.

He readily acknowledged that The Yard’s budget numbers are fluid and subject to change. Factors including inflation, supply bottlenecks and interest rate hikes are complicating the outlook for developers nationwide.

ARPA has been a “saving grace,” he said, but it’s a one-time opportunity.

He said he hopes The Yards can be a model for other developers. But no model will work if costs keep climbing, delays keep lengthening and restrictions keep multiplying.

“Just think about how many more units we could produce,” he said, “if we could do it in a more cost-effective way.”