(This article is part of One United Lancaster’s reporting on the 2023 Lancaster County Climate Summit.)

The challenge of climate change can seem impossibly daunting, Eric Sauder said.

Given the magnitude of the problem and the technical and political barriers to solving it, it’s easy to feel hopeless.

But Sauder believes there’s reason for optimism, especially in Lancaster County.

“There’s a path to carbon neutrality in Lancaster,” he said, and by taking it, the county can not only build itself a more resilient future, it can become a model for communities nationwide.

Sauder is the founder and executive director of Regenall, a nonprofit with the mission of making Lancaster County carbon-neutral by 2040. On Saturday, he delivered the opening keynote at Regenall’s Lancaster County Climate Summit, the first edition of what Sauder hopes will be an annual event.

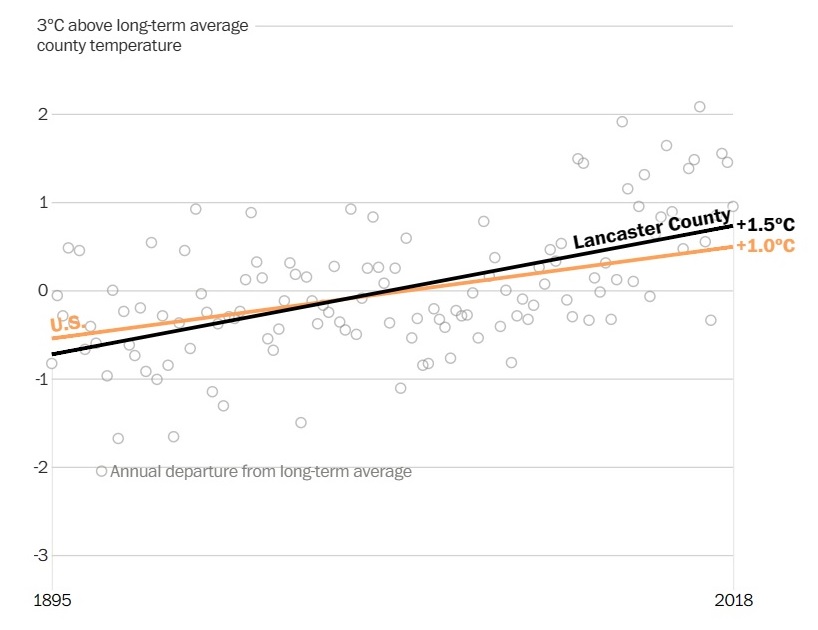

Since 1895, average temperatures in Lancaster County have increased by 1.5 degrees Celsius, equal to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, according to federal data reported by the Washington Post.

That warming trend plays out in more frequent 90-degree days, more intense storms and changing seasonal patterns, even as the region remains more buffered than many others from climate change’s more severe effects.

In 2020, Regenall published a greenhouse gas inventory for Lancaster County. Based on 2018 data, it indicated the county emitted the equivalent of 10.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide.

County households and institutions spend $2.5 billion on fossil fuels a year. That’s the equivalent of an Extra Give every other day, Sauder said, and almost all of that money is leaving the county. Imagine, he said, if Lancaster County kept that money here by building out its clean energy capacity.

Sauder gave rapid overviews of what households, businesses and farms can do, respectively, to reduce their carbon footprints, such as shifting to all-electric infrastructure or contributing to a carbon offset fund like Regenall’s Community Climate Fund.

In many cases, funding for retrofits is available from the Inflation Reduction Act, though Sauder noted the law really only gets the U.S. to the “starting line” in terms of what climate analysts say is needed.

Regenall has been working hard to crunch the numbers, using the approach exemplified by the Project Drawdown initiative. Preliminary results suggest that converting to heat pumps, rooftop solar and electric vehicles would yield some of the largest benefits, as would tree intercropping.

Lancaster County has experience in developing collaborative approaches to solve environmental issues, Sauder said: Namely, Lancaster Clean Water Partners, the coalition tackling stream health and pollution reduction in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

“We need to do very similar work” on climate, he said.

He painted a picture of a carbon-neutral Lancaster County in 2040, some 17 years from now. It is a hotter, stormier county — the next few decades of global warming are pretty much baked in — but it has the systems in place to withstand it.

It’s a county with thousands of family-sustaining climate-related jobs and an electric-vehicle microtransit network. It has healthier landscapes, waterways and air and is poised to enjoy the ongoing benefits of its clean-energy investments for decades to come.

That future Lancaster, he said, recognized that the climate issue could be a unifying force for positive transformation.

“The big shift, really, was in our collective imagination,” he said.