As Millersville University’s “Zero Hunger” summit proceeded from session to session last week, a set of consistent themes emerged:

- Despite Lancaster County’s role as a center of agricultural production, food insecurity is widespread;

- Combating it is a challenge that requires collaboration, creativity and humility;

- Food providers must continue to reduce any and all barriers to access, including the stigma that many people feel around accepting assistance.

Held Thursday at the Ware Center, the regional summit was the latest conference convened by the university in connection with its “Global Goals for Sustainable Development.”

The daylong event brought together professionals from area schools, colleges, nonprofits and government agencies: In all, 150 people were registered, Millersville Vice President for External Affairs Victor DeSantis said.

Over the course of the day, they explored the scope of food insecurity in Lancaster County and the efforts to ameliorate it.

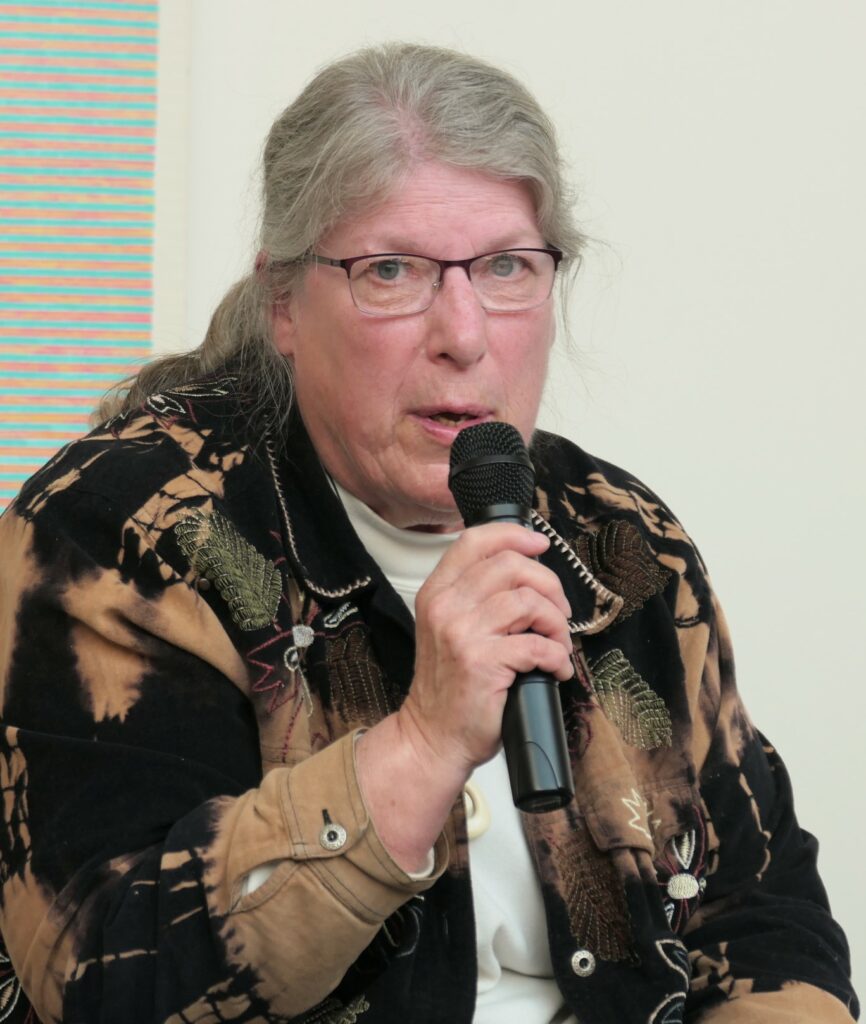

Central to the discussion was the framing of food as a human right. That has important implications, social work professor Karen Rice said. In particular, she said, it commits organizations to “five key concepts”:

- Human dignity: Seeing individuals as worthy of assistance and giving them autonomy to make their own decisions;

- Non-discrimination: Ensuring policies and practices are such that assistance is available to all, regardless of circumstances

- Participation: Affected individuals’ voices should be heard in policymaking — Rice quoted the disability rights slogan, “Nothing about us without us.”

- Accountability: Organizations must hold themselves accountable, but also others, including elected officials, Rice said.

- Transparency: Ensuring that communication about the resources that are available is full and accurate and is reaching the people who need to know.

Zero Hunger summit: Additional coverage

The scale of the problem

Senior Policy Research Manager Zach Zook leads the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank’s research team, whose goal, he said, is “to bridge the information gap.” One need, he said, is to use “evidence-based mechanisms” to look for intersecting and upstream issues with food insecurity.

“We can bring forward best practices and serve our neighbors, recognizing their needs in Lancaster County,” he said.

According to the food bank’s research, one child in eight in Lancaster County is food-insecure. In Dauphin, Lebanon and Berks counties, the numbers are even higher.

One in four single-parent households is food-insecure, while survey responses indicate that 23% of visitors to food banks skip meals periodically.

Food insecurity is correlated with unemployment, household income, disability and poverty. Over the past quarter century, it has waxed and waned, but it has proved exceptionally difficult to drive the core measure below 10%, Zook said.

The numbers shot up in 2008, in the wake of the Great Recession, and remained elevated for years. Now, with pandemic-era assistance having expired and inflation having driven up food costs, need is expanding again.

“It takes sustained strategic investments to really make a dent,” Zook said.

‘It’s peace of mind’

Vanessa Philbert, CEO of Community Action Partnership (CAP), centered the day’s discussions around what food insecurity means, and how to improve community response.

Food insecurity, said Philbert, is part of a complex hierarchy of needs that people have to think about as they assess what’s important in life.

She mentioned both Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Satter’s hierarchy of food needs, which adapts Malsow’s ideas.

“It’s not fancy vacations,” she said, as an example of whether people feel that they are fulfilled. “It’s peace of mind.”

She asked: What does it mean for us to have enough? Do we aspire for others to be beyond just ‘enough’?

“Hunger is (related to) the way that we have access to food,” she said urging people to think about neighbors and friends and whether they may be experiencing some type of food insecurity, and suggesting that there is a direct correlation between food security and quality of life, as well as length of life.

She discussed her personal experience and the culture of food, with the example of her family making traditional meals according to Puerto Rican tradition for years.

In a house of three generations of women, she said, the experience was living in the margin between ‘enough’ and ‘acceptable.’

She talked about the experience of using old food stamps back when that’s what they were: Color-coordinated bills in a booklet. It was sometimes difficult, she said, for recipients to use them in public, where the process was obvious enough to get noticed at the cashier’s station.

Today, she said, a lot of work around food security is trying to change the ways that people access food.

“We’re trying to create space for choice,” she said.

Homefields Care Farm

Homefields is a unique nonprofit with multiple missions: It is a 19-acre farm where individuals with disabilities help to grow organic produce.

Homefields is Lancaster’s oldest Community Supported Agriculture enterprise, said Carol Welsh, chair of the Homefields board. It also provides nature and agriculture education programming and volunteer opportunities to hundreds of community members. Six people with developmental disabilities live on site.

Homefields recently launched a program with Millersville University to grow asparagus and ramps in the spring to support Millersville’s Hunger Free Campus initiative. The university is underwriting the initiative with a $2,500 grant from its Positive Energy Fund.

“Our business is really people and engaging all types of people in organic farming,” said Walsh, who took part in a panel discussion at the “Zero Hunger” summit focusing on nonprofits’ role in combating hunger.

“If there’s anything that you want to learn, or teach to the families that you’re working with, please communicate with us,” she told her audience. “We would love to have you.”

Linking food, health

In a later panel discussion, Julie Rhoads, vice president of health and nutrition at Community Action Partnership of Lancaster County, offered a checklist of tips for supporting people in poverty.

Providers should rigorously examine their own attitudes and their own practices, Rhoads said. Families shouldn’t have to repeatedly document their need, or feel demeaned for accepting assistance.

CAP has four major components to its health and nutrition programming: It is the county’s WIC provider and operates a mobile pantry; it runs SNAP-Ed, a nutrition education program for SNAP recipients; it operates two senior centers that provide meals; and it is a food distribution hub, supplying 40 local food banks with more than half a million pounds of food a year.

Diet is implicated in the most common chronic diseases that Americans suffer from, Rhoads said: Heart disease, diabetes, obesity. In other words, better food security and better nutrition are part of the broader battle to improve health outcomes.

Midway through the day, attendees took part in a paper-and-pencil role-playing exercise. Participants were given information on a family’s earnings and circumstances, then had to budget and pay bills from week to week, coping with unexpected adversities along the way: A lost job, an unexpected illness. The exercise was offered by CAP and was an abbreviated version of a poverty simulation that the nonprofit makes available to community organizations.

In coming days, Millersville plans to draft a white paper summarizing the summit and post it and the various presentations on the event web page, DeSantis said.